In this post I take a look at Aged Care from a financial point of view. Some may think that by the time you go into Aged Care you are living out the last years of your life and your finances are not a high priority. However I think the finances of Aged Care are worthwhile investigating in order to get answers to the following questions:

- To what extent is the quality of Aged Care available to you dependent on your financial assets. i.e. should you try to preserve assets to pay for aged care?

- If Aged Care quality does depend on your financial assets, how much should you try to preserve?

- If one partner goes into Aged Care while the other is quite healthy, how does Aged Care impact on the finances of the person not in Aged Care?

- If both partners eventually end up in Aged care, or if one remaining partner is in Aged Care, how does Aged Care impact on the amount left to beneficiaries?

After the analysis in this post, I answer these questions in the conclusions.

What is Aged Care?

Aged care is care for the elderly regulated by the Federal Government and can take several forms. These forms are:

- Help at Home. In this type of care, you remain in your home and Aged Care staff visit you to provide assistance required.

- Short Term Help. This type of care is provided when you have a temporary set back which means you require some form of additional care.

- Residential care. In this type of care, you move to a residential care facility and are provided with care 24 x 7.

The type of Aged care I will focus on in this post is Residential Aged Care. The costs of other forms of Aged care do impact on the costs of Residential care because certain costs are capped across all types of Aged Care. This means that if you are provided Home care, for example, and then move into Residential Care later, your costs in Residential Care may be lower. If I have time, I’ll look at other forms later.

Aged Care is subsidized by the government and means tested. If you have assets or income above government defined thresholds, you will need to contribute some of your assets/income towards Aged Care. As mentioned above, some of these costs are capped, meaning that if you are in Aged Care for an extended period, costs may be less.

The Aged Care system is the responsibility of the Federal Department of Health. This government department provides the funding to support Aged Care services, regulates the costs of the services, manages the accreditation of the Aged Care homes and oversees the legislation for Aged Care.

This web site provides details of the Aged Care services provided in Australia, while this site is also quite useful. Information on other forms of Aged Care may be found at these sites as well (e.g. Home Care).

Who uses Residential Aged Care?

The diagram below shows the proportion of the population that uses Residential Aged Care:

You can see it is used mostly by people over 85, and also females tend to outnumber males. Also, in all likelihood, the average person probably won’t use Aged Care at all.

Here is a diagram showing the number of people entering into Aged Care by age:

Most people don’t come out of residential aged care alive!:

The diagram below shows how people leave by length of stay. The longer you are in an Aged care home, the more likely you are likely to leave as a result of death.

All of the above diagrams are sourced from here.

This diagram shows that most people coming into Aged care are on the Pension:

Most females are widowed , and most males are married:

If residents last the first 6 months, they are likely to stay longer. Note that 48% of males are only in Aged care for less than 12 months.

The above diagrams are sourced from here.

How do you get access to Residential Aged Care?

In order to get access to Aged Care Service you must:

- Register with “My Aged Care” by calling the My Aged Care contact number on this site.

- Based on your conversation with the My Aged Care representative, you may be referred for a formal assessment.

- Assuming the result of your assessment is referral to an Aged Care home, you then:

- Work out the costs

- Find an Aged Care Home

- Apply and accept an offer

- Enter into agreements, and then

- Manage your services.

More information may be found on the “My Aged Care” web site.

What are the Residential Aged Care cost components?

Aged care costs can take a while to understand (this was certainly my experience!). I’ll try to make them a simple as possible. Because the Government subsidizes aged care, there are lots of rules around access to this care. One important thing to note is that one way or another you will get into Aged Care if you need it (even if you have no assets).

Aged care costs are made up of three major components. These are:

The Basic Fee

The Basic fee is 85% of the Basic Single Pension and as of March 2017 was $48.44/day.

It’s a fee that everyone is required to pay. You will normally have no difficulty paying this fee because of access to the Aged Pension (or other assets if you are not eligible or only partially eligible).

Note that once a couple are separated due to one entering an Aged care home, if the couple are eligible for the Aged Pension as per income and asset limits (which are the same as the couple limits at present), each person will receive the Single Pension. The maximum assets at which the part pension cuts out are presently slightly higher than a normal couple in this instance.

The Means Tested Care Fee

The Means Tested Care fee is an additional fee that covers care based on your assets and income.

Some important notes about the means tested care fee, and its interaction with the Aged Pension are shown below:

- The Means Tested Care Fee depends on your assets and income. The value of your assets and income for the purposes of the Aged Care asset and income tests are derived in much the same was as the Aged Pension income and asset assessments (although there are some important exceptions, refer below).

- If you are married, your joint income and assets are divided by 2 for the purposes of working out Aged Care assets and income.

- If you still own your PPOR, the value of this asset is capped at $159,631 (at March 2017) from the point of view of the Aged Care asset test.

- If you have a “Protected Person” in your home, then the value of the home is not included in the Aged Care assets test. A Protected Person is:

- A spouse or dependent child

- A carer who is eligible to receive an Australian Income Support Payment, who has been living there for at least 2 years

- A close relative who is eligible to receive an Australian Income Support Payment and who has been living there for at least 5 years..

- Assuming a protected person is not in your home, once you move into Aged Care your home can be exempted for up to 2 years under the Centrelink Aged Pension assets test but will be assessed for Aged Care immediately.

- If you are a member of a couple and your spouse leaves the family home, but does not leave due to illness or Aged care, the home ceases to be exempt from the Aged Pension assets test after the longer period of:

- 12 months from the date the spouse vacated the home

- Two years from the date the resident entered Aged Care.

- If you are a member of a couple and your spouse remains in the family home while you enter Aged care, you are considered to be a home owner for the purpose of the Aged Pension asset test.

- If you are a member of a couple and your spouse remains in the family home while you enter Aged care, and your spouse dies, a two year Aged Pension asset exemption period for your home commences on the date of the spouse’s death.

- If you are in Aged Care, and you retain your home and do not have a protected person in the home, you are considered to be a home owner for the purposes of the Aged Pension asset test for 2 years from the date of entering Aged care, and a non home owner thereafter.

- If you are in Aged Care and single and sell your house, you are considered to be a non home owner for the purposes of the Aged Pension asset test.

- If you are in Aged care and a member of a couple, and your partner is not in Aged care and the house is sold with the intention of buying another home, you are considered to be a home owner for the purposes of the Aged Pension asset test for 12 months from the date of the sale. If a new home is not purchased within 12 months, you will be considered to be a non home owner.

- If you keep your home and rent it, your net rent will be assessed for both Aged Care and Centrelink Aged Pension.

- The Refundable Accommodation Deposit, the amount you put down for your accommodation (more on this in the next section) is included as an asset when computing the Aged Care means tested care fee, but not the Aged Pension.

- The Aged Care means tested care fee is capped at $26,041 (March 2017) per year. There is also a lifetime cap on the Aged Care means tested care fee of $62,499 (March 2017). The cap is indexed.

- Gifting rules apply to the method of calculating the Aged Care means tested care fee, the same as the Aged Pension.

- Financial assets are deemed to generate income, as per the income Aged Pension test.

- The Aged Care means tested care fee changes as your assets change. As your assets go down, the means tested care fee will be reduced.

- The Aged Care means tested care fee can be no more than what the govt would pay for care (Subsidy and primary supplements). I’m still looking to clarify what the Govt subsidy actually is.

Some good information about the treatment of the family home and its impact may be found here.

Here is a diagram showing the Aged Care means tested care fee as a function of assets and income. Note that I have assumed that the Aged Care means tested care daily fee is capped at $26,401/365 = $72.33. This is not strictly true as in practice the fee will could be higher in the first part of the year and zero in the remainder (but averaging out to $72.33)/day, assuming you don’t die!).

The formula used can be found in the End Notes of this post. The area circled in red is where there is no Means Tested Care fee.

The Accommodation Fee

The accommodation fee is the fee which is used to cover the capital cost of the accommodation. When you are assessed as eligible to enter Aged Care, you will need to apply to Aged Care homes for suitable accommodation. The amount you have available in funds will be a factor in determining your acceptance. The accommodation will usually consist of a room, which may or may not be shared with other residents and may or may have dedicated or shared toilet facilities. The value of the fee is refunded to your estate when you leave the Aged Care home, less any additional fees incurred (more on this later).

Aged care homes are not allowed to price accommodation at more than, in Mid 2018, $550,000 unless exempted by the government authorities.

Aged care homes publish the price of accommodation on this web site:

https://www.myagedcare.gov.au/service-finder/aged-care-homes

Here are some examples in Sydney:

| Facility |

Location |

Room Name |

Room Type |

Cost |

Extra Service Fee |

Cost of room + Extras |

Comment |

| Uniting Kari Court |

St Ives |

Secure Living |

Single Room + ensuite |

$503,000 |

$0 |

$79.38 |

|

| Bupa |

St Ives |

Premium |

Single Room + ensuite |

$800,000 |

$0 |

$126.25 |

24-25 Sqm, BIR, King Single Bed |

| Bupa |

St Ives |

Superior |

Single Room + ensuite |

$775,000 |

$0 |

$122.30 |

As above |

| Uniting Wesley Gardens |

Belrose |

Spacious Living |

Single Room + ensuite |

$510,000 |

$0 |

$80.48 |

|

| Uniting Wesley Gardens |

Belrose |

Companion Living |

Shared room and shared bathroom |

$421,000 |

$0 |

$66.44 |

Max 2 occupancy |

| Uniting Wesley Gardens |

Belrose |

Secure Living Banksia |

Single Room and ensuite |

$452,000 |

$0 |

$71.33 |

|

| Uniting Wesley Gardens |

Belrose |

Companion Living |

Shared room and shared bathroom |

$390,000 |

$0 |

$61.55 |

Max 4 Occupancy |

| Turramura House |

Turramura |

Private Single |

Single Room + ensuite |

$400,000 |

$64 |

$127.12 |

|

| Turramura House |

Turramura |

Premium Single |

Single Room + Shared bathroom |

$300,000 |

$56 |

$103.34 |

|

| Turramura House |

Turramura |

Deluxe Single |

Single Room + Shared bathroom |

$200,000 |

$56 |

$87.56 |

|

| Turramura House |

Turramura |

Standard Shared Room |

Single Room + Shared bathroom |

$100,000 |

$56 |

$71.78 |

|

| Unniting Mullauna |

Blacktown |

Spacious Living |

Single Room + ensuite |

$429,000 |

$0 |

$67.70 |

|

| Blacktown Nursing Home |

Blacktown |

Level 2 Southern Extra |

Single Room + ensuite |

$380,000 |

$30 |

$89.97 |

|

| Blacktown Nursing Home |

Blacktown |

Level 3 Northern |

Shared Room + no bathroom |

$325,000 |

$0 |

$51.29 |

|

| Blacktown Nursing Home |

Blacktown |

Level 3 Southern |

Single Room + ensuite |

$380,000 |

$0 |

$59.97 |

|

| Blacktown Nursing Home |

Blacktown |

Level 3 Northern A |

Shared Room + no bathroom |

$250,000 |

$0 |

$39.45 |

|

You can pay for the accommodation in a lump sum, a daily fee or a combination. The daily fee is an interest fee on the outstanding amount owing, using an interest rate of 5.76% (as of March 2017). Once signed-up, the interest rate does not vary. The amount you pay as the lump sum is known as the Refundable Accommodation Deposit (RAD), and the daily fee is known as the Daily Accommodation Payment (DAP). As of Mid 2018, the average RAD is about $320,000, and the average DAP is around $60. The refundable fee is refunded to your estate when you leave Aged Care.

Note that, assuming you pay the full RAD, the Aged Care home is essentially being funded by the interest on the RAD. If the inflation (and likely interest rates) should vary during your stay, you will be getting a good (high interest rates) or bad (lower interest rates) deal.

Instead of you paying the RAD, it is possible for a family member to pay it in the form of a loan. However in this circumstance, the RAD is included as an asset and not offset by the loan. Also, when the resident dies, the RAD is refunded to the member’s estate, so appropriate legal contracts should be in place.

When you pay the lump sum for the accommodation, you must be left with at least $46,500 in assets (as of March 2017). If you choose to pay only a part of the lump sum, you don’t need to have the income or the assets to cover the full value of the outstanding amount; if you run out of assets or income stops, then the daily fee can be taken from the principle i.e. the lump sum you have already paid (a bit like a reverse mortgage). As you are most likely to stay at the Aged Care home for a comparatively short period (e.g. 2-3 years) you typically don’t need a lot of cover. What happens if you run out of principle? Well, this is an interesting question and I haven’t found the answer to this. It may be that Aged Care homes are unlikely to accept you if this is a possibility i.e. you will need to look for a cheaper room or maybe they will put you in a cheaper room when you run out of capital.

What happens if you have no money at all (or very little)? Well, we mentioned at the beginning that everyone will get access to Aged Care one way or another.

If your income and assets are in the red are circled in the Means Tested Care Fee diagram above, then you are classified as a “Low-means Resident”. In this case there is a different formula to work out how much to pay, and the fees will be heavily subsidized by the government. Note that once classified at a Low-means resident you will always be one (even if you win the Lottery!).

When you enter an Aged Care home you may not immediately have the funds to pay the RAD (e.g. if you have to sell the home at short notice). When you enter the facility, you have 28 days to decide to pay for the accommodation. If within those 28 days you decide to pay a RAD, you have 6 months to pay. If you make a decision after 28 days to pay a RAD, it is due as agreed between yourself and the home. DAP is to be paid in the interim.

Additional Fees

In addition to the three major cost components described above, aged care homes may also offer chargeable additional services. These could include, for example, hair dressing, premium meals etc. You can see these fees in the examples provided above. In some cases these additional fees may be significant!

Fee Changes

Fees are increased twice a year – 20 March and 20 September, in line with increases in the Age Pension.

Questions I still don’t know the answers to!

After extensive research on the Internet there are still a couple of questions for which I do not have answers (despite all the blurb on the Internet!), mainly around criteria aged care homes use for acceptance and how the marketplace for Aged care works.

Let’s say you are Single and have $250K in cash as your only asset. You would like a reasonable quality Aged Care home and notice that a room becomes available in a nearby Aged Care home, and the RAD is $400K.

Now, you could actually afford this by:

- Putting down a RAD of $200K.

- Using the remaining $50K to fund the DAP (which would be $31.65/day), although not 100% sure this is allowed e.g. it could be reserved for medical expenses etc. Note however, that the use of the principle certainly is allowed.

- Paying a means tested care fee of about $9.50

- Receiving the full single Aged Pension to pay the Basic Fee.

The remaining $50K, if used to pay the DAP would fund about 4.3 years (more than the average duration in an Aged Care home of about 2.5 years). After this the Aged Care home could take money from the principle, which is permissible, to find the accommodation payment, which would fund many more years.

Let’s say you only have $150K. Then you could:

- Put down a RAD of $100K.

- Use the remaining $50K to fund the DAP (which would be $36.59/day).

- Means Tested fee would be zero.

- Receive the full single pension to pay the Basic Fee.

Again the $50K would fund about 3.7 years of living, and the $100K many years after this.

My question is are these arrangements common or accepted by Aged Care Homes? If so, what is the typical amount of funded years that is acceptable?

And what happens in the unlikely event that you live longer than the funds permit?

This article states that this practices does occur, and here is an extract:

Aged Care Steps technical manager Lara Hansen says that if paying the RAD in full isn’t feasible and there are only enough assets to fund a partial RAD payment, then they could also elect to deduct the DAP from the RAD paid.

“This removes the DAP from cashflow requirements by deducting from the RAD instead. This will result in slightly more aged care fees over time, as the DAP is calculated on the unpaid RAD. As the unpaid RAD decreases the DAP will increase,” says Hansen.

It also means a reduced lump sum payment back to the estate at the end, which in Cronk’s case would mean a reduced final retirement savings pool.

Here is a diagram showing the number of years of funding assuming that the shortfall in the DAP can be funded by remaining funds not used for the RAD and the RAD itself (in that order). The number of years is capped at 18. If funding from the $50K is not allowed, each item in the “Amount of Capital” axis will need to be increased by $50K.

Here is a diagram showing the amount of capital required to fund a room of a given value, assuming the Aged Care home uses the criteria that at least 5 years of funding is available from the RAD and the additional funds (approx $50K) which is not allowed to be put towards the RAD:

You can see that to afford a room worth $400,000, for example, you only need about $110K of capital. If the funds not allowed to be put forwards for the RAD (About $50K) is not allowed, then the amount in the “Amount of Capital” axis would need to be increased by $50K. In this case, to afford a $400K room, you would need about $160K of capital.

Maximum or Minimum RAD?

In this section I look at the question of how much of the RAD you should pay, assuming you have at least some funds to pay it. Should you pay the RAD, or should you pay the daily fee (the DAP)? In this section I look at payments for the first year only.

Assets in Superannuation

Minimum RAD

First, let’s assume that you are Single (couples will be similar, but assets will be divided by 2) and you have all your assets in Superannuation and you are looking at a room with a contract value of $400K.

If you pay no RAD, then you must cover the payment with the Daily Fee. Here are the components of your the Aged care fee in this case:

You can see that if you had $1,000,000 in Super, for example, the total fee would be about $60K per year. Note the means tested care fee is about $17K and if you stay in the home long enough, this may reach the lifetime $62K cap. Also, for each year you stay, the means tested fee will be reduced due to the declining assets.

How much of this fee will be covered by other sources of income? We show the Aged Pension in the below graph, and also show the income that would be derived from the money that would otherwise be in the RAD (i.e. retained in the Super system), and assume a 6% return:

You can see that there is no Aged Pension eligibility at high levels of assets. This is because the total Super assets are high.

Maximum RAD

OK, now lets assume that you pay the most RAD that you can and again the contract value of the room is $400K.. Remembering that you must leave about $50K outside the RAD, here is the diagram showing the fee:

You can see there is now no accommodation fee where this RAD can fully cover the cost of the room and the overall fee is quite a bit lower. But we would expect the fee to be lower because we are no longer generating income from the Super invested in the RAD.

We can also show how much of the above fee is covered by other sources of income (in this case, the pension):

Note that even with the example of $1M in financial assets, there is still some pension payable. In this case the RAD is not included as an asset for the purpose of the Aged Pension test.

Comparison of the approaches

We can now compare the two approaches in terms of the amount payable after taking into account other sources of income (e.g. Pension, Super returns for funds not invested in the RAD):

There is a clear winner. It’s best to maximize the RAD.

The reason that it’s best to maximize the RAD is that the money you put towards the RAD does not cause the Aged Pension to go down and it means you do not have to pay the accommodation fee. The accommodation fee (the amount you pay if you pay no RAD) is about the same as the money earned from Super (the money you keep if you pay no RAD ). The maximize RAD strategy is better because you get more of the Aged Pension.

Other Asset classes

The above analysis assumed that funds were in Superannuation as this made the analysis quite a bit easier (e.g. no Tax!). In reality most people will be selling their home and will be at an age where it is not possible to invest the funds into Super.

If the funds are invested in bank deposits the returns are likely to be lower, and if the funds are invested in Super-like assets (e.g. Exchange Traded Funds etc) then the returns are likely to be similar or lower due to Tax. In both cases, the advantages of maximizing the RAD will be exacerbated.

Approaches to Funding Aged Care Funding

In this section I look at various common scenarios and some strategies on approaching Aged Care funding. I look at the strategies for Single people and Couples and look at them using three criteria:

- The comfort of the person going into Aged care (i.e. the quality of the room etc.)

- The amount of funds left to beneficiaries

- The impact on the remaining person not in Aged Care (for couples)

Lets look at the Single Person first.

The Single Person

Single Person in their own home and on the Aged Pension, no other assets

Most people will enter aged care late in life, and it is likely that they will have few assets at this time, so I believe this will be a common scenario.

Selling the House

The most obvious solution in this case is selling the house and using the proceeds to fund a RAD.

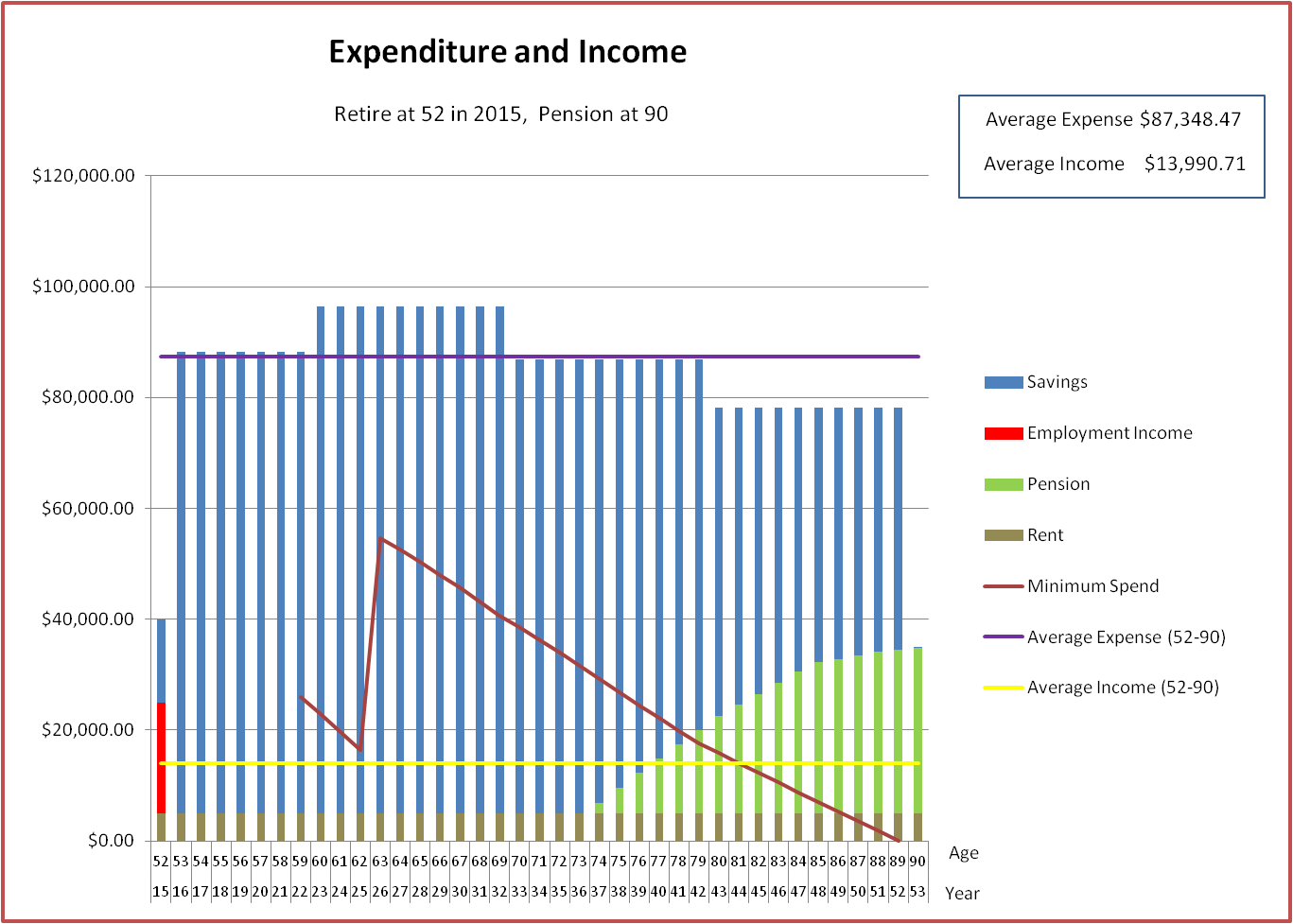

A high end or low end room could be purchased. Lets look at each case in a hypothetical scenario. We’ll assume the house is worth $1,000,000 in each case, the proceeds are held in a bank account generating 3% returns and inflation is running at 2%. We’ll also assume the person in Aged care does not have any additional expenses and each of the various parameters used to calculate the Pension, the means tested care fee etc goes up with inflation.

High End Room

Lets assume that the room is priced at $700,000 and the person going into Aged Care pays the full value of the RAD. In this case the Pension will be high, but there wont be much income generated from the Bank account.

Here is a diagram showing the income (Pension, Bank Returns) and costs (Means Tested Care Fee, Basic Fee, Tax) associated with this scenario (adjusted for inflation, and also, for simplicity, assuming the Means Tested Care Fee is only adjusted yearly). I also assume that the Means Tested Care Fee cap does not change with inflation once you commence Aged Care.

You can see the Means Tested Care Fee trailing off as the cap is reached. After 4 years the value of the assets has been reduced to about $902K (adjusted for inflation – i.e. in the dollars at commencement), or about equivalent to $25K per year.

Low End Room

Now let’s assume that we choose a low end room with a RAD of $350,000. In this case the Pension will be low and the Means Tested Care Fee will be a similar amount. But we will get some funds from Bank interest.

In this case, total value of assets has been reduced to $893K after 4 years, which is lower then than the high end room.

A comparison of total assets by Room RAD

This diagram shows the value of total assets after 4 years by value of the RAD:

You can see the optimal value is around $500K. The reason that the optimal is in the middle is because if the RAD is too low, the Pension goes down, and if it is too high then you still get the full pension that would be available from a lower RAD, but don’t get the interest from the bank.

This diagram shows the value of total assets by value of RAD by length of stay in the Aged care facility:

You can see assets declining as time goes on, but the asset decline decelerates after about 4 years (as the Means Tested Care Fee cap is reached). There also seems to be a sweet spot of about $500K for the RAD.

Keeping the House

What about keeping the house.? If the extended family wants to keep the house in order to avoid transactions costs and to keep it as an inheritance, one strategy would be to keep the house, and rent it out. How would this strategy fare?

Here are some rules relevant to this scenario:

- If you still own your PPOR, the value of this asset is capped at $159,631 (at March 2017).

- Your former home can be exempted for up to 2 years under the Centrelink Aged Pension assets test but will be assessed for Aged Care.

- If you keep your home and rent it, your net rent will be assessed for both Aged Care and Centrelink.

There are some other rules which are relevant to this scenario:

- In most states, Land Tax will be payable on a home that is rented out. I’ve added this in on the assumption that this is about $4K per year, net of any taxation offsets.

- Capital Gains Tax is payable on the sale of the house, but only if the property is rented out for 6 years or more.

- Assuming the property is rented out for a period of less than 6 years, the beneficiary of the property can receive a CGT exemption if it is sold within 2 years.

These rules don’t look too good. Let’s assume you keep your PPOR of $1M and rent it out for a net of $30K per year. We’ll assume a capital growth on the house of 3%.

In this case the pension and the after tax rental income in most cases do not cover the Means Tested Care Fee, the basic fee and the accommodation fee. For the purpose of analysis, we’ll assume that we can get access to funds at approx 5.77% to cover any shortfall. These funds may be made available from a reverse mortgage, and the recently announced Federal Government Reverse Mortgage scheme may be a good choice.

High End Room

Let’s assume we enter into an agreement for a $700K room, and, as all our assets are tied up in the house, we pay the DAP.

Here is the diagram showing the costs and income:

You can see the costs are quite a bit more than the income due to the high value of the accommodation payment. Also, the part pension (already small due to rental income) disappears after year 2 because the exemption of the PPOR Aged Pension test expires after this. The MTF also disappears in year 3 due to the income becoming lower due to the pension being removed, and also the cap on the PPOR. Also relevant to this scenario is the change from homeowner to non homeowner status for the purpose of the Aged Pension asset test after year 2 (although in this case, there is no pension payable after year 2 due to the home being included in the assets test after year 2!).

After 4 years the net assets are about $918K.

Low End Room

Now let’s again assume a low end room of $350K. Here is the diagram showing costs and income:

There is a similar pattern, except now costs are closer to income. Due to the capital growth of the house, the net assets after 4 years are about $1.01M.

Comparison of Total Assets by room RAD

Comparison of different RADs and length of stay

Here is a diagram showing how the net assets vary by different RADs and different lengths of stay using the rental approach:

This is quite a bit different than the house sale strategy and here you can see that, if you wish to preserve your assets, it is better to get a cheap room (especially if you are planning to live for a while!).

Selling the House versus Renting

Finally here is a diagram showing net assets under each of the two approaches:

Surprisingly a rental approach is better than a selling one in most cases (and, taking into account transaction costs for selling, even more so).

The reason this is surprising is that we showed earlier that, at least for the first year, it was better to pay as much of the RAD as possible (in this case the RAD is not counted as an asset when working out the Aged Pension; if we don’t purchase the RAD the funds are counted as an asset). Keeping the house and paying the DAP is kind of like selling the house and not paying the RAD, so we might have expected this strategy to be worse.

When we compared maximizing the RAD with Zero RAD, we only looked at the first year. The diagram below confirms that it is quite a b it worse for other years as well (at least in this situation):

The reason that the result of renting the home and paying the full DAP does not have a similar outcome to selling the house, putting the proceeds into a bank account, paying zero RAD and the full DAP is that, by renting the home:

- The house is not counted as an asset for the purposes of the Aged Pension asset test for 2 years from the date of moving into aged care. You are likely to get an Aged Pension for this period.

- The value of the house is capped at approx $159K from the point of view of the Means Tested Aged Care Fee. Hence this fee is not likely to be very large.

Other Strategies

There are other strategies, and some of them are described here. These involve annuities, trusts etc. If I have time, I may come back to these.

The Single Person with assets other than the family home

Another common scenario will be a Single person with other assets, such as Superannuation or an investment property. Each of these will need to be handled on their merits, and working out the best approach can use similar tools to that shown here.

Summary for the Single Person

In summary, I have looked at two scenarios, one where a single person has their own home valued at $1M and this person sells it to fund Aged care, and another whereby the a single person has their own home valued at $1M and it is rented with any shortfall funded by a reverse mortgage.

In the case where the single person decides to sell the home, the best strategy to preserve assets is to pay the full RAD for a room priced at around $500K. There isn’t much asset loss if a contract for a higher priced room is entered into, so if there is a room at a higher price that is significantly better, there may be a case for a better quality room.

In the case where the single person decides to rent their home, the best strategy to preserve assets is to enter into a contract for the cheapest room possible.

If there is a choice between selling and renting, the best strategy, from an asset preservation point of view, is to rent out the house and stayer in a cheaper room. However, if the length of stay is envisaged to be 6 years or more, it may be better to sell.

Of course if asset preservation is not an issue, then go for the best room possible!

The Couple

Couple living in their own home with no other assets

When a member of a couple goes into Aged Care and the couple does not have assets outside the family home, then, assuming the home is not sold, the person going into the Aged Care facility will be treated as a low-means resident. Their Aged Care service will be provided by the Single person Aged Care pension which they will be receiving once they have entered the home. The family home will be exempted from the Aged Care means test as there is a protected person in the home. The person remaining in the family home will start receiving the Single Age pension.

What if the person moving into the home would like a better room? One approach is to use a Reverse mortgage. We looked at these here.

Reverse Mortgages

Let’s assume the couple are living in a house worth $1M and one member is going into Aged Care, and a decision is made to fund the costs of Aged Care with a reverse mortgage with the funds drawn down as required (i..e not a lump sum). One good thing about this approach is that there is no impact on the Pension, and the income stream received from the Reverse Mortgage is not included as assessable income and therefore does not contribute to the MTF, and the PPOR is not included as an asset from either the Aged Care or Aged Pension point of view.

Let’s look at the financial impact of this approach. Here are the income and costs associated with entering into a contract for a $700K room, assuming a reverse mortgage rate of 6%. Note that the overall cost for 4 years is about $156K.

Here is a diagram for the income and costs for a $500K room. Cost for $500K room over four years is approx $105K.

And here is a diagram for the income and costs for $350K room. Cost for a $350K room over four years is approx $67K.

And finally, here are yearly costs for a variety of types of rooms:

You can see the cost increasing over the duration of the stay. The reason for this is the compounding interest on the reverse mortgage.

One important thing to note about the reverse mortgage is that interest costs continue to grow in a compound way even after the member of the couple has left Aged care.

Couple living in their own home with other assets

What if the couple has other assets? Well in this case the other assets can be used to fully or partially fund the room, with a reverse mortgage used to top up living expenses for the remaining member of the couple as required. This strategy makes sense because otherwise the assets may reduce the pension or increase the MTF.

Summary for a couple

In summary, we have shown that when one member of a couple goes into aged care, a viable strategy may be to use a reverse mortgage to fund the costs of Aged Care. Costs increase in a roughly linear fashion as the value of the room increases.

Our Strategy

Our Strategy may vary according to when (and if!) one of us needs to go into Aged care, and our finances at the time. Assuming we stay in the PPOR until we die (as described in one of the approaches here) and, for the sake of argument, I need to go into Aged care at the age of 85, we will most like sell the investment property (about $380K) to fund Aged care. and maybe use some of the Super to top up the amount used to fund the RAD from Super. At this age will are estimated to have about $237K in Super, which is not a great amount! Alternately we could sell the primary home with one member going into the investment property and the other going into Aged Care.

Overall Conclusions

At the start of this blog, we asked:

- To what extent is the quality of Aged Care available to you dependent on your financial assets. i.e. should you try to preserve assets to pay for aged care?

- If Aged Care quality does depend on your financial assets, how much should you try to reserve?

- If one partner goes into Aged Care while the other is quite healthy, how does Aged Care impact on the finances of the person not in Aged Care?

- If both partners eventually end up in Aged care, or if one remaining partner is in Aged Care, how does Aged Care impact on the amount left to beneficiaries

To what extent is the quality of Aged Care available to you dependent on your financial assets. i.e. should you try to preserve assets to pay for aged care?

From our examples you can see that the more funds you have available, the better quality room you will have (i.e. not shared with others, dedicated ensuite etc). I don’t really have enough experience with seeing the actual quality of accommodation and care to determine if the paying the extra is worth it. In addition, the utility of the accommodation versus the cost will vary by person, so this question will need to remain partially unanswered.

We do have an elderly relative in Aged Care with a room value of $500K and and additional service fee of $70/day. The facility is excellent, but the fees are very high!

If Aged Care quality does depend on your financial assets, how much should you try to reserve?

Again, this question is difficult to answer as it depends on the utility of the accommodation versus the cost. We did see that:

- The Government presently caps the value of accommodation at about $550K, but there is an exception process.

- You do not need to pay for the full value of the room because fees can be drawn from the RAD. We saw that to afford a room worth $440K, for example, you only need about $210K in capital (assuming that an Aged care home will accept you if you have 5 years of funding, and also that the $50K in assets not eligible for putting into the RAD cannot be used to fund daily fees).

If one partner goes into Aged Care while the other is quite healthy, how does Aged Care impact on the finances of the person not in Aged Care?

We saw that for the couple with low amounts of funds but having the family home, the use of reverse mortgages can help with improving the quality of care for the person going into aged care. For a couple with a family home worth about $1M, for example, the cost of a $500K room would be about $25K per year (including interest, accommodation fee etc). Once the resident left Aged Care, additional fees would be ongoing because of the outstanding interest on the Reverse Mortgage amount. We also saw that the person going into Aged care could do so at zero cost and no reverse mortgage assuming the low means resident accommodation provided was acceptable.

If both partners eventually end up in Aged care, or if one remaining partner is in Aged Care, how does Aged Care impact on the amount left to beneficiaries

Taking a single person with a family home worth $1M, and few additional assets as an example, we analysed two strategies to funding Aged Care. These are selling the home and keeping the home and renting it.

In the first strategy we saw that, in terms of preserving assets, that it was best to enter into a contract for a room worth approximately $500K. This also has the happy coincidence of providing a good quality room. We also saw that it was sensible to pay a much of the RAD as possible.

In the second strategy, we saw that, in terms of preserving assets, it was best to enter in a contract for a room with the lowest value possible.

When comparing these, we saw that, in terms of preserving assets, it was better to use the rental strategy in most cases but especially so if a cheaper room was deemed to be acceptable and the duration of the stay was expected to be short.

Putting it online

Aged care funding is complex and is another excellent candidate for online calculators.

End Notes

The formula used to compute the Aged Care payments may be found here. The basics are also shown below.

Means Tested Care Fee

To work out the Means tested care fee, you need to work out the values below.

Income Tested Amount

Income Tested Amount = (0.5 * (Income – Income free Area Amount)) / 364

Asset Tested Amount

Asset Tested Amount is

0 if Assets < Asset Free area Amount

(0.175 * Assets) / 364 if Assets > Asset Free Amount and Assets < First Asset Threshold.

(0.175 * (First Asset Threshold – Asset Free Area Amount) + 0.01 * (Assets -First Asset Threshold)) / 364 if Assets > First Asset threshold and Assets < Second Asset threshold

(0.175 * (First Asset Threshold – Asset Free Area Amount) + 0.01 * (Assets -First Asset Threshold) + 0.02 * (Assets – Second Asset Threshold)) / 364 if Assets > Second Asset threshold.

Means Tested Amount

The Mean Tested Amount = Income Tested Amount + Asset Tested Amount.

Means Tested Fee

Means Tested Fee = Means Tested Amount – Maximum Accommodation Supplement Amount

At the time of writing, the thresholds and other constants above are:

Income free Area Amount = $25,711.40

Asset Free Amount = $46,500

First Asset Threshold = $159,423.20

Second Asset Threshold = $385,269.60

Maximum Accommodation Supplement Amount = $54.29

Accommodation Subsidy

The Government will pay up to the Maximum Accommodation Supplement Amount ($54.29) per day towards your accommodation. However, the means tested amount is the maximum of zero and the Maximum Accommodation Supplement Amount – the Mean Tested Amount.

Interest on unpaid RAD

The interest on unpaid RAD is .00576 * Value of the unpaid RAD (per year).

Asset Threshold

A resident must be left with at leadt $46,500 after choosing a RAD level..