In this post I go through a process to work out if my wife and I have enough assets to retire. The aim is to understand if we can retire now, or if we need to continue to work. I also consider the impact on our retirement of working additional years, of poor performance of our Super, of taking some time off living in a country with a low cost of living, of spending our money and deciding to go on the Age pension early, and of taking out a lifetime annuity rather than an account based pension. I also look at the riskiness of the proposed early retirement plan by looking at how the plan would have fared in various historical scenarios.I do this for my case and it might be similar to yours.

Some background

I am married and have no children. My wife doesn’t work and I am an IT professional. We are presently living in a foreign country and we intend to return to Australia in a year or so. I am 52 and my wife is a few years younger. We will probably do some traveling prior to returning. On my 52nd birthday (near the end of 2014), we had these assets:

- About $530K in superannuation,

- A house worth about $1 million,

- About $595K in cash,

- An investment property worth about $250K which brings in about $5K per year and

- Another property in a seaside town we intend to retire to.

We don’t spend much money and this last year only spent about $30K (costs are lower here!). Under the plan in this blog, I will stop working in Feb 2015, and then stay the rest of the year in this country. We will then think about going back to Australia.

We plan to spend about $40k in 2015. This plan works out how much we can spend in subsequent years.

What we would like to do in Retirement

We both enjoy traveling, but we don’t need to travel in style, i.e. budget travel is fine with us. We are contemplating taking the opportunity of traveling for maybe 6 months after we leave here before coming back to Australia. We also like walking in the Australian bush and reading, and my wife has many hobbies while I like working on the computer. We don’t really have any high expense hobbies other than traveling.

Resources that are available to help with working out if you have enough money to retire

When I started doing research into when I could retire, I looked around the web for resources that could help. Most commercial superannuation sites have planners, but most only permit limited scenarios to be modeled. For example, most don’t allow asset sales, or for you to exist on savings prior to accessing your Super.

Planners generally fall into one of two categories. Those that try to work out how much you can spend given the age at which you intend to live only on the Age Pension (a type I planner), and those that work out how long your savings/superannuation will last given the amount of spending per year you are proposing (a type II planner). The former is more useful, but generally a lot harder to implement.

This planner on the ASIC Moneysmart site is a quite useful planner. It includes the Australian Government Age Pension and is a type I planner.

https://www.moneysmart.gov.au/tools-and-resources/calculators-and-apps/retirement-planner

AMP also has another good calculator. It also includes the Age pension and is a type II planner.

https://www.amp.com.au/calculators/myretirementsimulator/index.html#!/

Firecalc is another resource that is also quite useful as it gives you an indication of the riskiness of investments linked to the markets:

http://www.firecalc.com/

Firecalc works out if you would have run out of money after 30 years if you had retired on a specific historic year, invested your savings in the stock market at that time, and spent a fixed amount (adjusted for inflation) for each subsequent year. It does this for every year from 1871 and lets you know in how many of them you would have run out of money. If you have surplus funds at the end of 30 years in all or most of the years, you should feel confident that your savings should be sufficient to fund your retirement if you invested in the stock market (or Super if you use the stock market as a proxy). Note that firecalc uses the historical performance of US markets.

Firecalc has many other features and I will investigate how these can best be used for Australian conditions in another post.

There are many planners around the web which will give you an indication of how long you and your spouse will live and this can be a useful input into Superannuation planners.

According to this one, http://www.mylongevity.com.au/, I will live to 84. Another one told me I will live to 86.

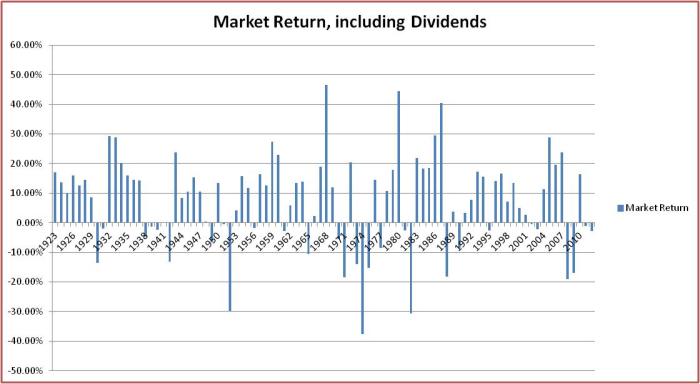

This diagram in the nytimes is quite interesting as it gives you an idea of the volatility of the markets:

http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2011/01/02/business/20110102-metrics-graphic.html?_r=3&

Also on numerous sites is the 4% rule. According to this rule, you can retire if your annual spending will be no more than 4% of your financial assets. So if you want to spend $50K per year, you will need $1.25M. Note that there is no length of retirement in this calculation. This rule assumes you can make 4% + inflation on your assets through investments, so that you never lose your capital.

Although I found all these planners and tools to be useful, I found that that they did not provide all of the information that I require to plan my retirement. In particular, the following is missing:

- Functionality – The planners do not cater for things such as asset sales, changes in spending patterns as we age, existing on cash prior to 60 etc.

- Sensitivity Analysis – How are my retirement plans impacted by varying some of the key assumptions – e.g. the age of stopping working, the age of spending all assets, the returns from Super etc.

- Products – The planners do not allow me to look at how I would fare using different products (e.g. lifetime annuity versus account based pension).

- Risk – The planners do not tell me how my plans are impacted by variable super returns, or how my plans would have fared in various historical scenarios.

- Baseline Plans – There is no ability to create a baseline plan and compare progress against the plan.

For these reasons, I have developed my own set of tools. While these tools presently consist of spreadsheets, if I have time available I will endeavor to put these online.

Australian Superannuation and Age Pension Rules

In the following sections, I have worked out how we will fare in retirement under various scenarios. I have strongly leveraged the information in the “Australian Superannuation and Age Pension Rules” post in this blog. It contains the Government rules that are applicable to early retirement. In order to fully understand our strategy and the various scenarios, you will need to familiarize yourself with these rules. These rules should also be useful for your own planning.

Our Retirement Strategy

We are planning to use cash to finance our living expenses until it runs out, then use superannuation, possibly supplemented with the Age pension. Before I hit 65 (about 13 years away), we will sell our house and put the funds in Super. We will take advantage of the “Bring Forward” superannuation rule to put the proceeds of the house sale into Super in one year. We will then move to either our investment house or our retirement house near the sea. We do not plan to sell our investment house.

My Calculations

In this section I work out the funds we can expect to be available to us each year, assuming we retire in early 2015 and we use the retirement strategy above. I have used Excel and Excel VB macros and the rules in the “Australian Super and Age Pension” post to do this. The Excel “solver” function is the critical function that I have used, as a complicated equation with boundary conditions is required to be solved.

For the purposes of the calculations, I have assumed that:

- We will spend 10% less per year when we hit 70, and another 10% less when we hit 80. The studies that I have read indicate that this is a reasonable, if conservative, assumption due to lower mobility when you age (and even taking into account higher medical bills). There is an interesting paper on this here.

- I will live to my 90th birthday and at this point we will no longer have any Super. After this if we are still alive, our only source of income will be the Age pension and rent.

- Inflation will run at about 2.73% per year. This is the average since 2004. This assumption will obviously almost certainly not hold true, but hopefully Super returns will compensate in the event of higher inflation.

- Rules relating to the Age pension don’t change. Again, this is unlikely to be the case. But I have based the calculations on existing rules as there is nothing else available and the rules when I retire will probably be similar to the existing rules. Some people have suggested that, in view of the uncertainty about Age pensions in the future, it may be best to model based on the Age pension being unavailable. I have done this modelling; you can see it here.

- Superannuation returns, nett of all fees, are 5.5%/year nominal, i.e. not adjusted for inflation. This is an equivalent of about 2.8% real return. Note that Australian Super balanced fund has averaged 8.69% per year since 2004, or about 6% real return, and this includes the GFC! (nominal – For each year from 2004 I have subtracted the inflation rate for that year and added in 2.73%, then averaged to get the 8.69%).

- On my 60th birthday I will move our Superannuation funds into an account based pension. As a result our Super returns will be improved due to lack of tax. I will assume that my Super fund was paying 8% in tax. So that means that after 60, returns on my pension will not be 5.5% but 5.5/.92 = 6.0%, or about a 3.3% real return.

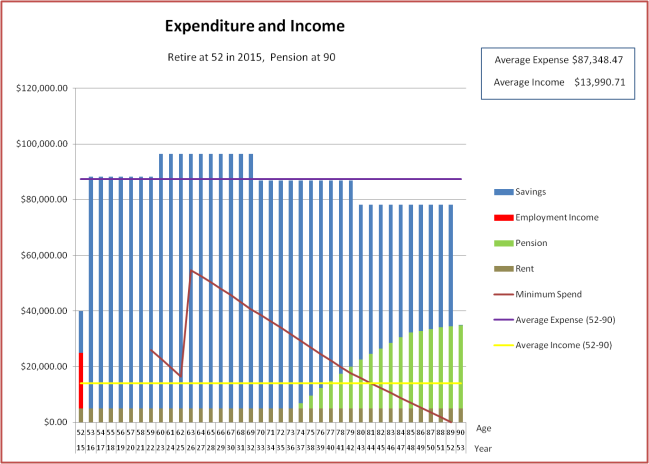

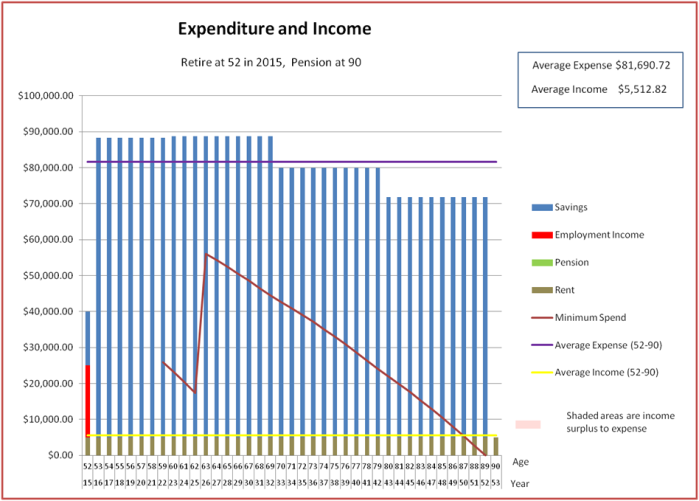

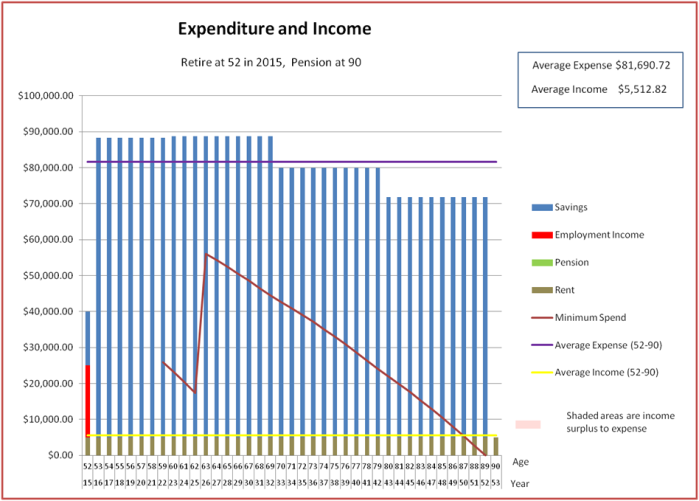

- We only spend $40K during 2015 and earn $20K (working for some of 2015) from employment and $5K from rent. Subsequent years involve spending the amount indicated in the graphs below.

- We sell our house just before my 64th birthday. This will leave a year’s buffer to ensure that we can move the funds into Super in time.

- Cash rate is 3.2%

- We continue to receive rental income from our investment property while we are alive.

- The rate of house appreciation is 2.83% (the average for my house over the last 10 years).

- We do not borrow any money or take out reverse mortgages.

- To work out our spend per year, we always maintain the same real value of spend year on year given the available assets over a particular time period and also given any planned changes in spending, with the goal of minimizing the available superannuation on my 90th birthday over the long run.

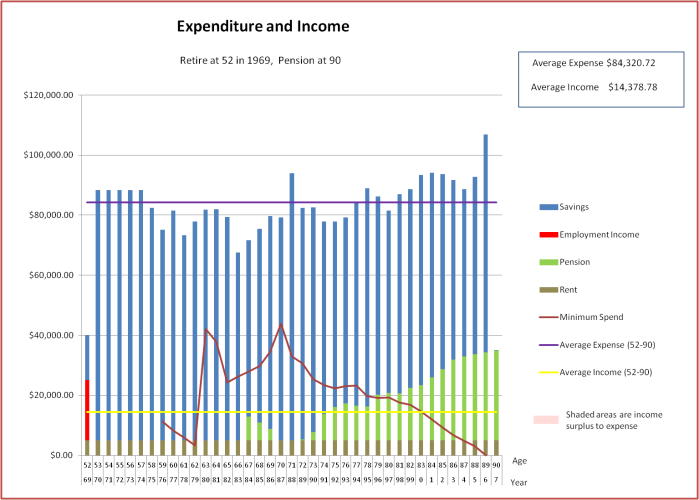

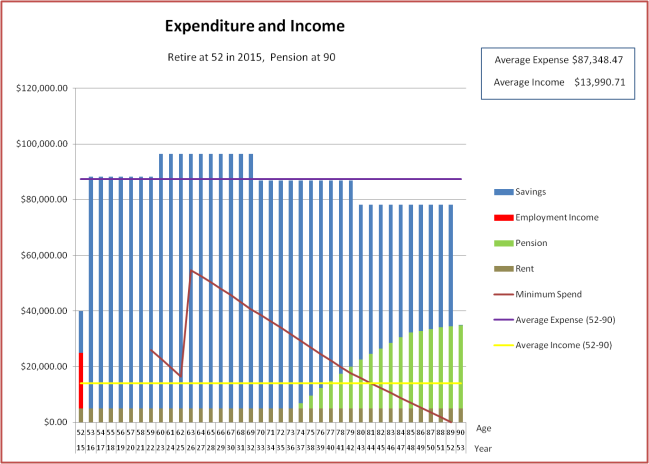

The graph below is the result. It is in real 2015 dollars. You can see the age pension kicking in at around 74. The spend prior to 60 is less than after 60 due to limited cash assets prior to 60. Average expense per year is about $87K. I’ve also included the minimum spend required by the account based pension. You can see that it is not a factor here.

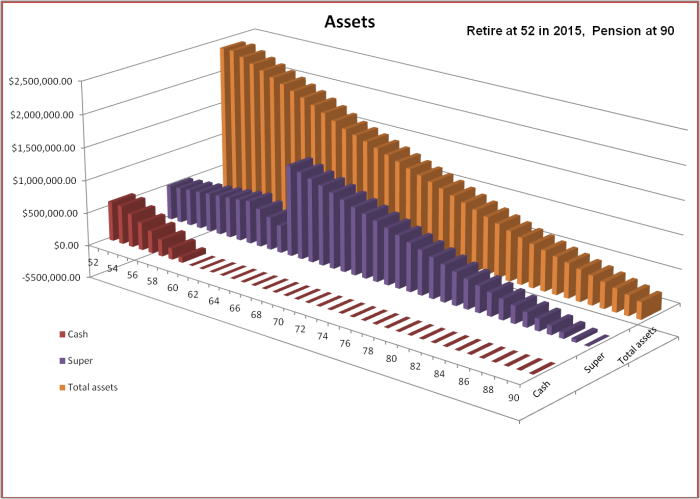

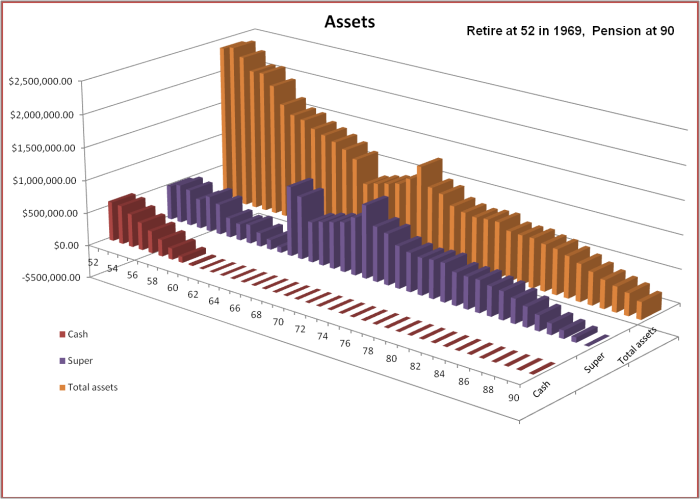

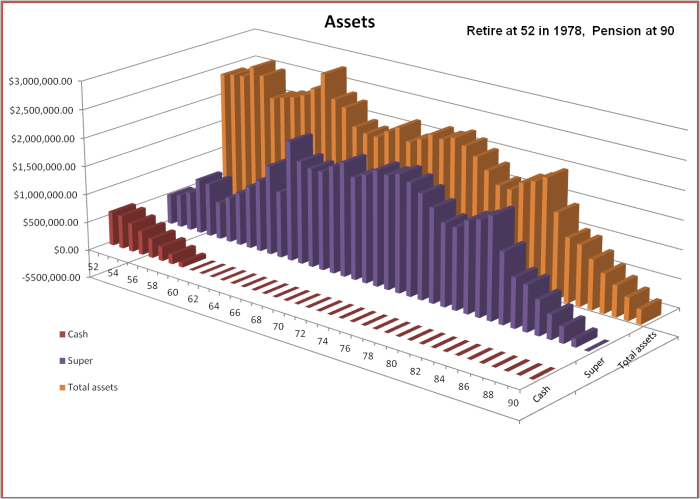

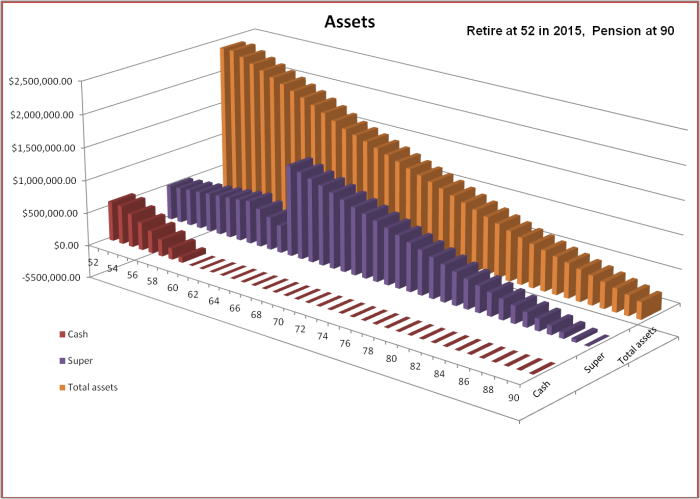

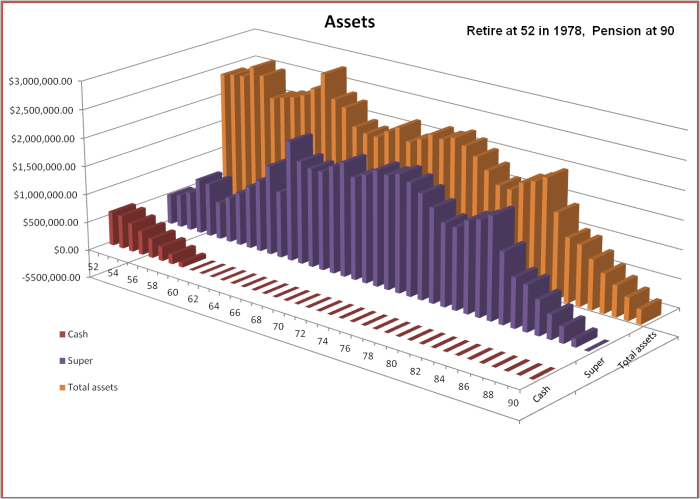

And here are the assets. You can see the super going to zero in the last year that we are planning to supplement the pension with Super. Total assets at 90 isn’t zero because we are planning to keep our investment property.

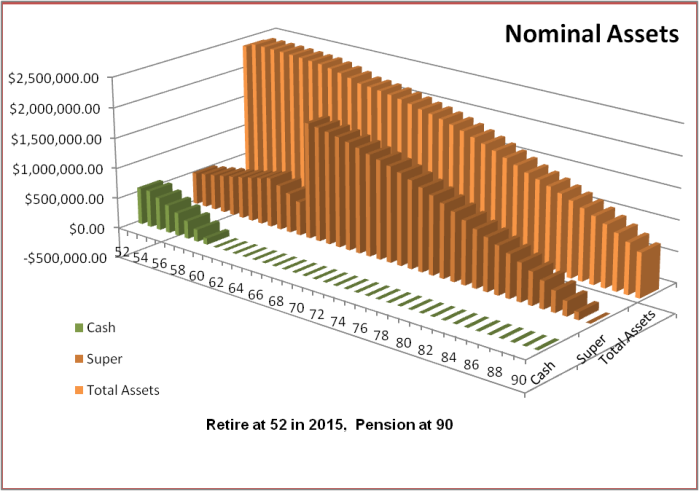

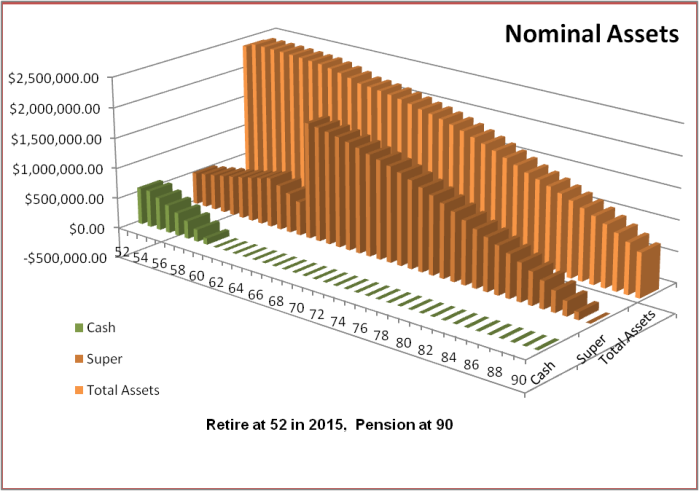

Here is the graph in nominal dollars (that is, not adjusted for inflation):

For those who are interested in such things, the way I have made the calculations is described at the end of this post in end notes.

Sanity Checks

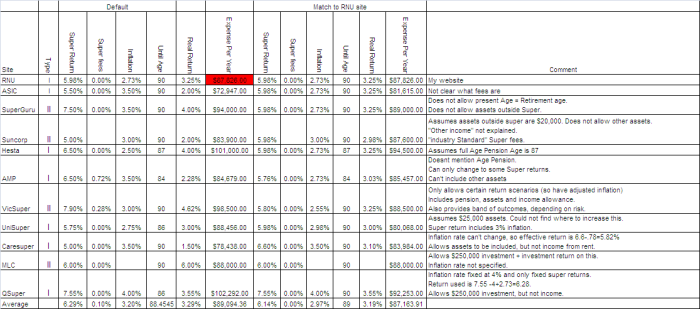

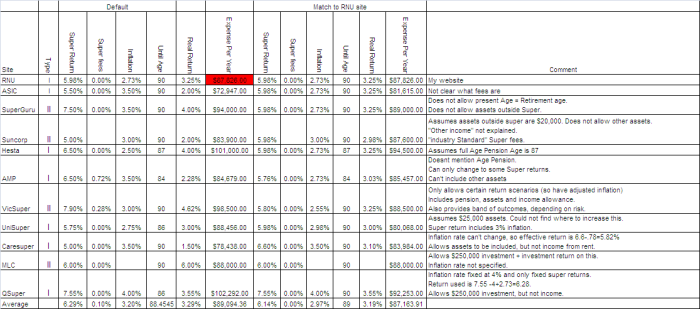

In order to check the results of the calculations are reasonable, I did some sanity checking by looking at the results of some online calculators and compared them with the results of my model. Due to the difficulty of some calculators with handling living on cash prior to accessing Super, and with asset sales, I started the calculations at 64. Also, most calculators can’t handle changes in spending profile over time, so I removed the reductions in spending at 70 and 80. I kept the investment property and the investment income as most (but not all!) calculators are able to handle this. If I do this, my model shows the Super level at 64 to be $1,409,596 and average spend to be $87,826 (both in 2015 dollars). If I enter these details (Super level, investment property, investment income) into the online calculators, as well as trying to make the inflation (2.73%), Super return levels (6.0%), fees (0%) and age when Super will last until (90) as close as possible to my model, I get the results summarized in the diagram below:

RNU is this website. Interestingly the ASIC site provides a much lower spend than most other sites.The above diagram shows that the results from my model are reasonable, with my site being very close to the average of all sites.

I also computed the spend using the calculator default inflation, Super return, fees and age at which Super lasts until. This results in an average spend increase of about $2000.

More details below:

Note that the average real default return (3.29%) is very close to my assumed real return (3.25%).

Which calculator did I like best? Actually the VicSuper one was quite good as it allows you to enter the investment property and investment income, and also provides a band of outcomes, depending on the riskiness of the investment. It is a “type II” calculator, meaning that you have to fiddle with the spending levels so that you get your funds lasting until 90. It doesn’t allow you to enter the Super returns level and only allows you to specify risk levels of the fund, but this is only a minor inconvenience.

Sensitivity Analysis

Having established that the results from my model are similar to those provided from other planning sites, I will now use the model to perform some sensitivity analysis around some of the key assumptions.

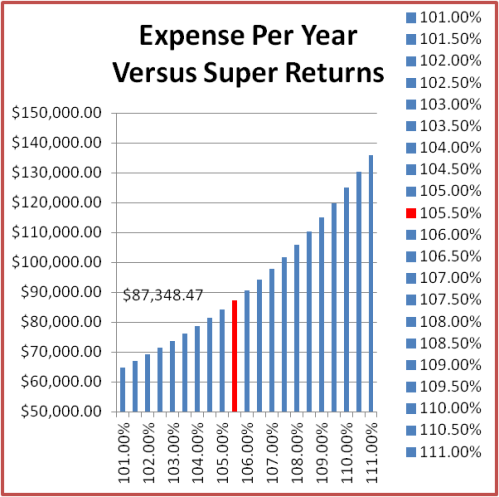

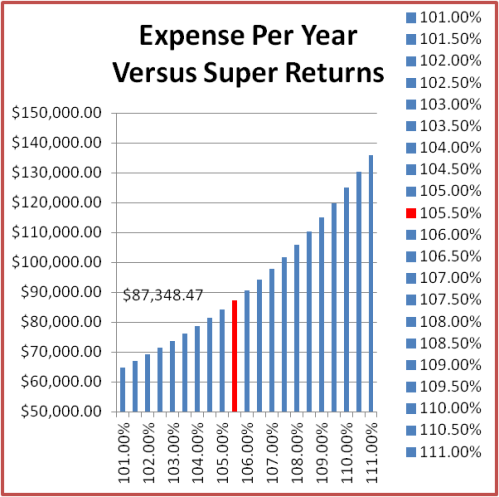

Here I worked out the sensitivity of the expense per year to Superannuation returns. Basically very sensitive. Later in the blog I look at how expense per year would have fared in some real historical situations. The super return rate I have used as part of my assumptions is highlighted in red.

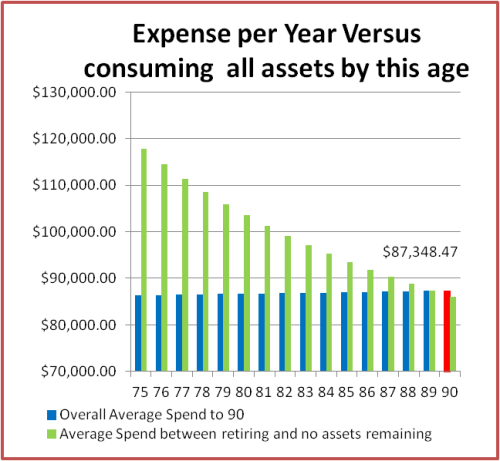

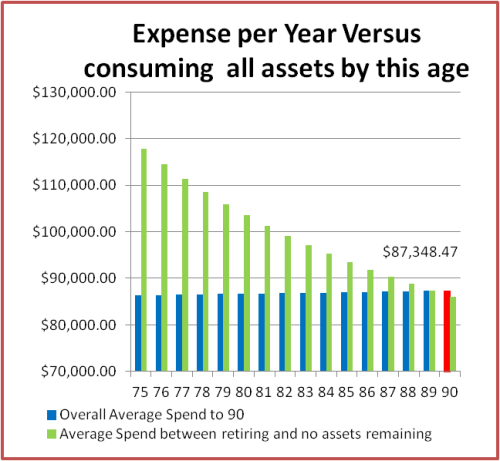

And here is the sensitivity to when we decide we will go on the age pension (i.e. when we are planning to have no super left). Not really too sensitive. I think 90 would be an OK age to plan for. The below diagram is saying that if we plan to spend all our money prior to 75, for example, we can expect a spend per year of just under $120K (rather than $87K). However after 75, we will be living on the age pension.

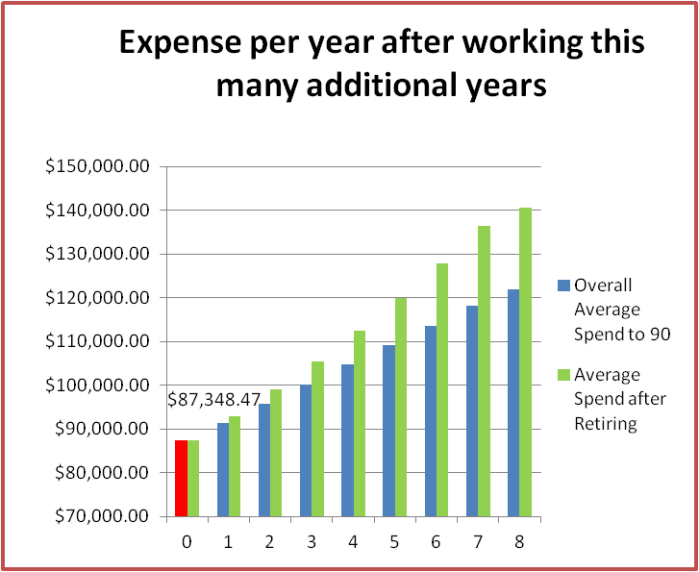

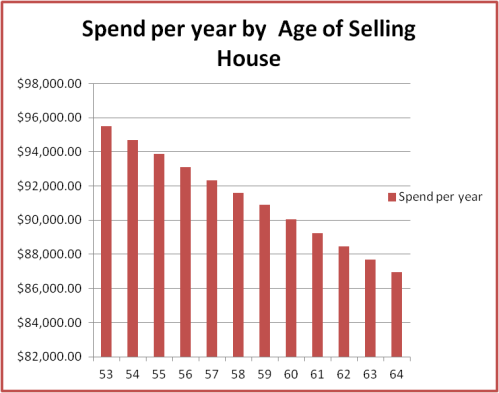

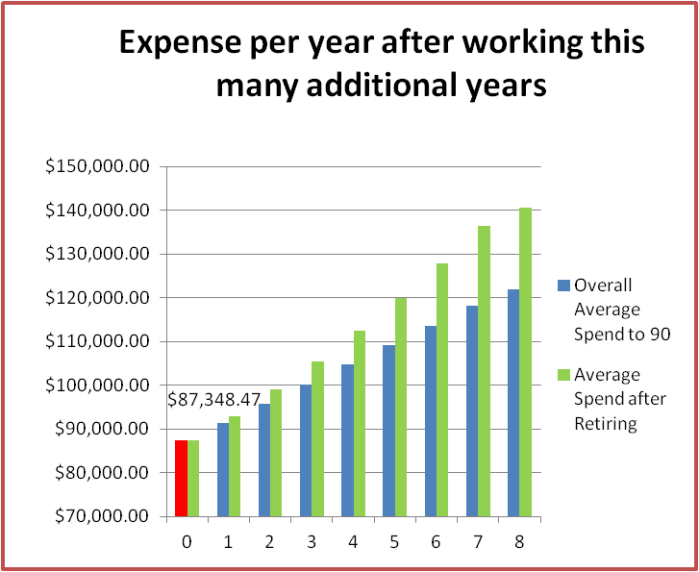

Then I worked out how sensitive the expense per year is to working additional years, assuming an annual expense of $40K per year while working, while still spending only $40k during the first year after stopping work. My average expense per year goes up by about $4.5K per year for every additional year that I work. The average expense per year goes up a bit more if I just consider the time after retiring.

Because the effect of working additional years is of particular interest to those considering early retirement, I have provided a summary of the details for each additional year of retiring here:

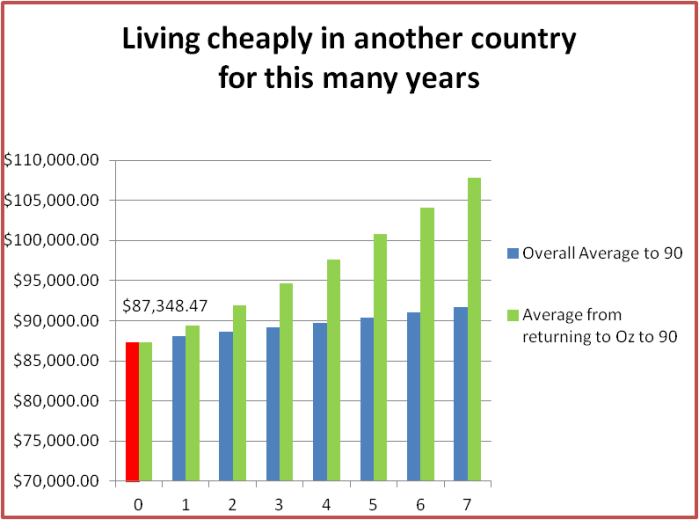

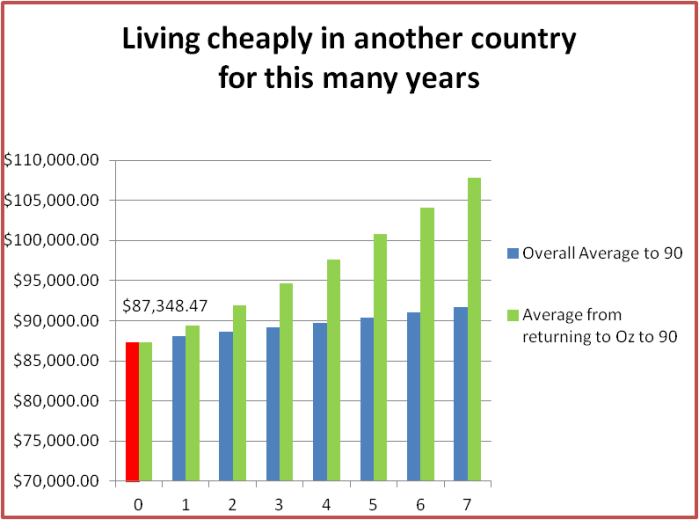

Lastly I looked at living in a cheap country for a number of years prior to fully retiring in Australia. Living in somewhere like Chiang Mai could be interesting. I assumed that we can live on $20K per year (+ rent from our property in Australia). You can see the average expense per year after we return doesn’t really go up much as a consequence. Note the rule regarding CGT on your home is applicable here.

Market Exposure and Risk

The next thing I did was to work out how risky this strategy is and how exposed to the market we are based on past performance of the market. The firecalc tool mentioned above is quite handy in this regard. However, I have added in support for Australian conditions, and also assumed that when our capital is reduced, we will also reduce our spending rather than spending the same fixed amount every year.

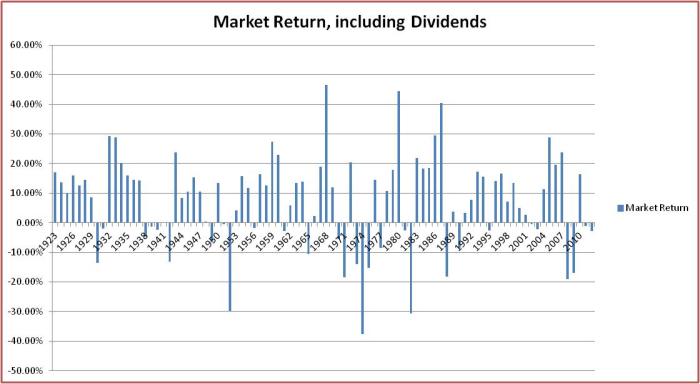

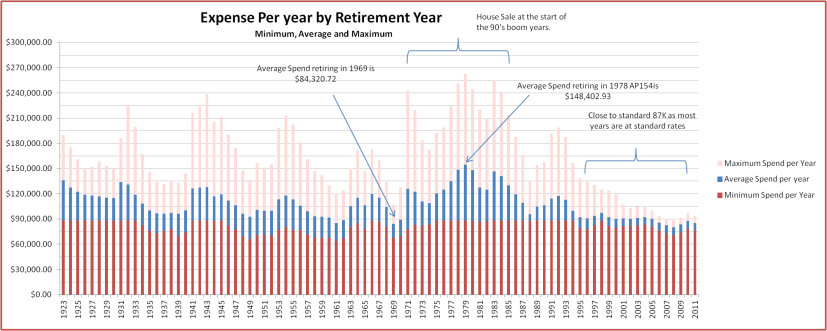

The idea is that I assume we retired at the start of a year between 1923 and 2012, and then worked out how much we would have available to spend that year based on the the assumption that the market would perform at 5.5% (pre 60) and 6.0% (after 60) for the remaining years with an inflation rate of 2.7% (just as I did at the start of the post). Next I look at the actual return for that year, work out the actual Super available at the end of year based on this return, subtract the amount spent during the year, and then repeat the calculation of how much I have to spend, again assuming the same return and inflation. I do this until I am 89. Note that the assumption of a 5.5/6.0% return only impacts the amount of money spent during a year, and does not impact on the actual performance of Super. The actual performance is taken from historic market returns. Also note that I am using raw market performance which is not moderated as a “balanced” superannuation fund would be.

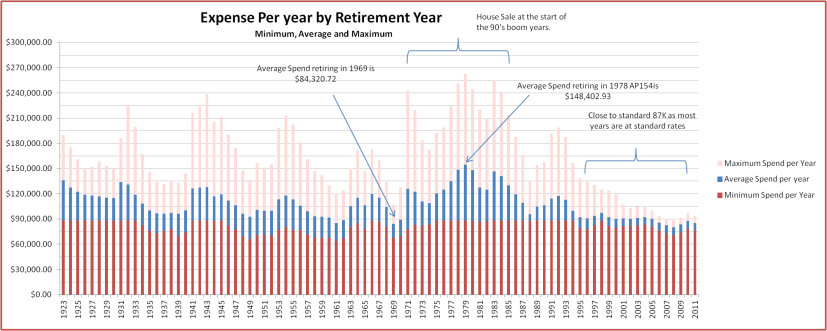

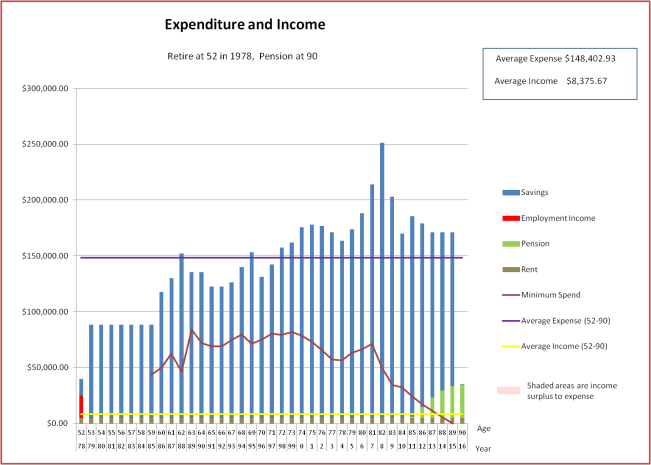

Anyway, If I do these calculations for each of the years between 1923 and 2012, it turns out that the worst year to retire was 1969 with an average expense per year of about $83K and the best year to retire was 1978 (getting the bull run of the 1990s when my house was sold) with an average of about $148k. The average expense per year across all years is about $105k.

I obtained historical information on the Australian market performance from here:

http://www.wrenadvisers.com.au/downloads/ (yxaoi.xls)

(I think there should be a better source than this, but could not find one).

I also obtained historical information on inflation in Australia from here:

http://www.rba.gov.au/inflation/measures-cpi.html

And also estimates of Dividends from here:

http://www.macrobusiness.com.au/2011/06/relying-on-stock-market-averages

Here is a summary of the extracted historical information (real returns):

Here is the average expense per year graph mapped out against retirement year. Excel took about 30 minutes to produce this graph due to all the Solver functions required!

Note that there is a cap on the minimum spend – that is because before 60 there is a cap on the spend per year due to the limited assets prior to 60. This spend per year prior to 60 can go down however, if Super performs poorly.

You can see from the above graph that in most years the average expense per year computed using actual market returns is a lot better than that computed using the assumed returns of 5.5/6.0% (i.e. 87k). In 9% of the years it is worse, but almost all of these years are recent because recent years assume a 5.5/6.0% return for most of the subsequent years (as there is no historical data). The only other that is not recent is in 1961.

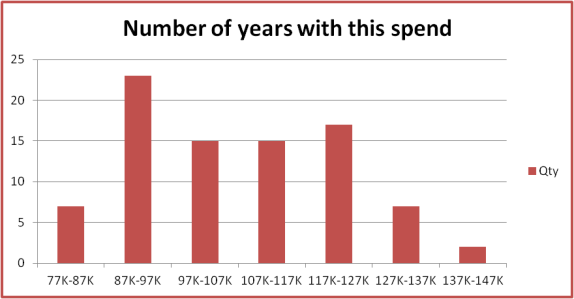

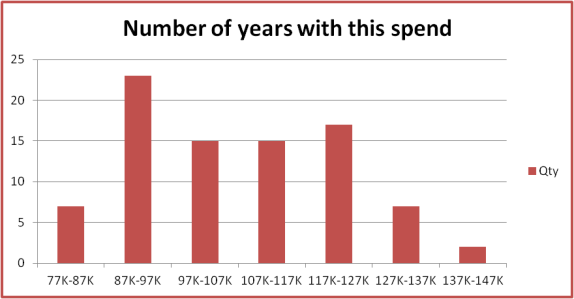

Here is a graph showing the distribution of average expense per year:

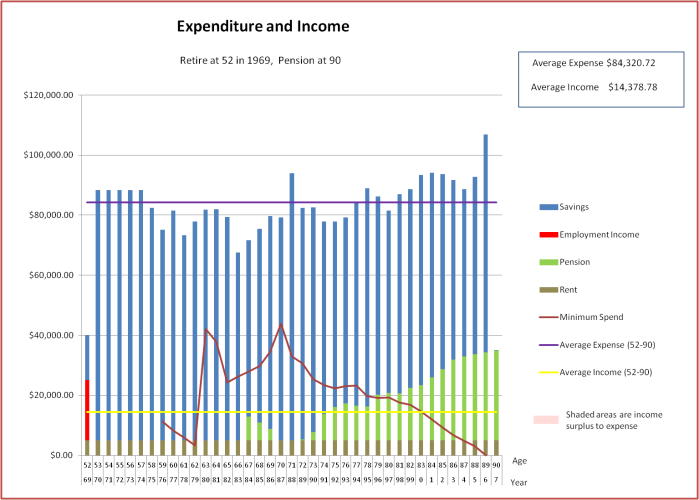

The below graph illustrates the expense per year for commencing retirement in the worst year (1969). Note the age pension cutting in a 67. Also note that in some years we only have about $67k to spend. The average of all the bars in this graph is about $83K, the value that corresponds to the 1969 bar in the expense per year graph above.

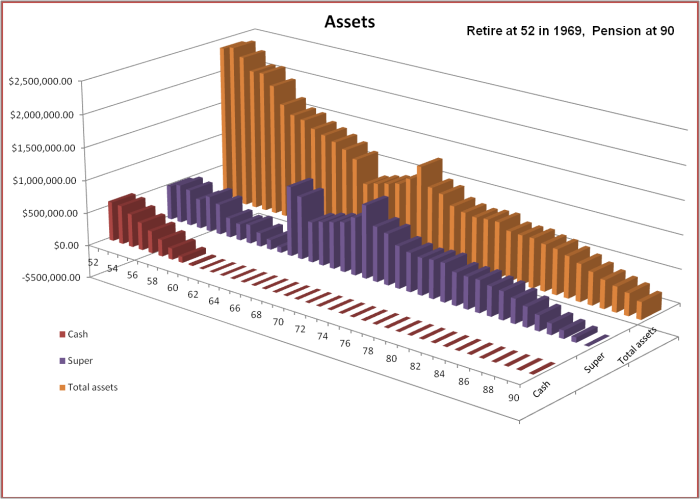

And here are the assets for commencing retirement in the worst year. Note also that the actual graph is nothing like the smooth graph assuming the constant return of 5.5/6.0% shown earlier in the blog.

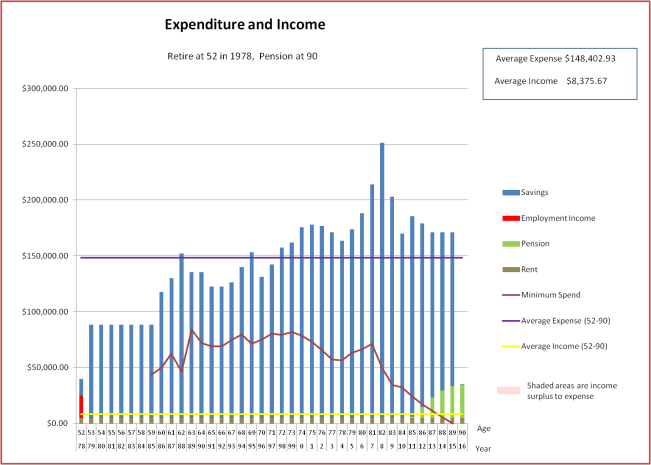

And here is the expense per year for the best year for commencing retirement (1978):

Note that the expense per year us flat prior to 60. This is because we are living on cash during this period prior to getting access to Super and the amount of cash is fixed. Also, the expense per year is flat after 2013. This is because we are now using the standard 5.5/6.0% rates (i.e. I have no market data after this).

And the assets for the best year:

Some people have commented that the reactive type of spending plan proposed here may not always be realistic as people often have fixed commitments which cannot be adjusted every year (e.g. golf club memberships etc.). However, at least in my case, our only high expense items we are planning is traveling, and we can easily cut back on this. I think cutting back in the event that Superannuation assets are reduced is a good idea. It prevents you from running out of money.

Lifetime Annuities

Most Australians either take out a lump sum, or purchase an Account based pension in their retirement. However there is another option, the lifetime (or fixed term) annuity. These types of products offer the advantage of income certainty, and also eliminate the risk of running out of money. The provider takes the risk.

How do strategies based on commercial lifetime annuity offerings stack up against my proposed strategy?

Using a popular Australian lifetime annuity product, I have chosen the income stream with full inflation protection starting from 65. In early 2015, this provides $3202 per annum for each $100,000 investment (for a male) until you die. It also provides a 100% income withdrawal guarantee, meaning that if I wish to withdraw the capital after 15 years, I get 100% of the capital back (unadjusted for inflation). 65 is the earliest published age at which rates are available, so I will assume that we will exist on the Account Based Pension to this age using the original plan, and then at 65 withdraw all the funds, and invest in the annuity. I will then compare the annuity with the account based pension after 65.

According to my model at 65 we will have $1,313,701 in Super in 2015 dollars. If I purchase the annuity with this asset at this age, then the annual income provided by the annuity after 65 would be $42,064. If I use half the money to pay for an annuity for my wife and half for an annuity for myself, and for the purpose of this exercise assume my wife is the same age as I am (as the company offering the annuity does not publish age-by-age annuity incomes), the amount would be $41,623. The amount is slightly less as females have a longer life expectancy than males. Note that a jointly owned annuity may give a better return, but the rates for this type of annuity are not available on the web site. Adding in rent received ($5,000) I can then work out the spend available each year using the annuity approach. To do this, I have used this section in Australian Super and Pension rules post. Note that:

- We cannot roll-over our Super Money to pay for the annuity as this is only possible if we have “unrestricted non-preserved funds”. I do have some of these type of funds, but only about $90K. Instead, we would have to take our Super out as a lump sum, and then purchase the annuity with these funds.

- As we will not be rolling over Super, we will have to pay PAYG tax on the income received. As the income received would only be about $23K each, and the “Deductible Amount” is higher than this (at least initially) and we also get an offset amount using SAPTO from Age Pension retirement age, there will be no tax to pay. If you had a higher income from the annuity, income tax may be a consideration.

- The Age Pension assets test uses the initial purchase prices of the annuities, less the “Deductible Amounts” accumulated to date as explained here.

- The Age Pension income test does not use deeming of the asset value. It uses the income from the annuity, less the deductible amount. As it appears that the deductible amount is not inflation adjusted, that means the income test becomes more important as you age.

Here is the graph showing the spend for the annuity:

Note that:

- The average spend for the annuity, assuming we both live to 90 exactly, is $63,800, while the estimated average spend for the Account Based Pension is $85,300. Or the annuity average spend is about 75% of the Account Based Pension amount.

- Barring changes to Government rules, the lifetime annuity amount of $63,800 is fixed and will not vary, while the Account-based Pension amount is variable and subject to market returns.

- The spending pattern is counter to the spending pattern that most people would like. That is most people would like to spend more in their earlier years and less in the later years.

- The Age pension starts to decline as you age, because the incomes test becomes more effective. The “Deductible amount” is not inflation adjusted so it becomes less effective in reducing the income from the annuity and therefore reducing the reduction to the Age Pension due to the incomes test.

If we live beyond 90, the lifetime annuity becomes more attractive, because with the Account Based Pension we will be living on the Age Pension (+rent) only, whereas with the lifetime annuity we will continue to be funded by the annuity. Still, the average income from the annuity only exceeds the estimated average income from the account based pension if we both live to 106.

The other way to look at the Lifetime annuity is to work out the present value of the payments from the provider assuming we live to certain ages. The graph below provides information on the age to which we would both need to live in order for the provider to lose money, assuming various discount rates..

An Alternate Strategy

One of my relatives has decided to sell up in Australia and go and live in Thailand for an indefinite period. Which makes me think about doing something similar. Perhaps selling up our house and maybe traveling for some time. Surely selling up and putting all the funds into Super would amplify our savings and give us a much higher spend per year? As a safety net, I have assumed that we will not be getting rent from our investment property once we have sold up (as we might live there). I also assume we will fully retire at 65 by living at our final destination.

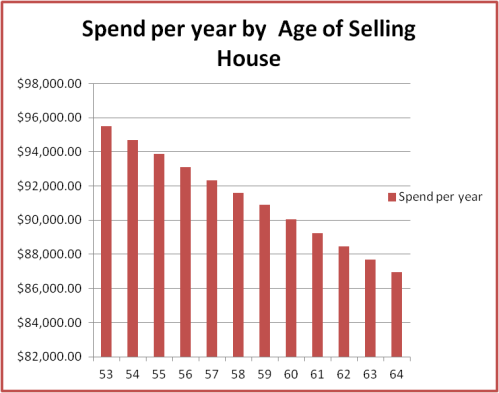

Well, I did these calculations and got the graph below:

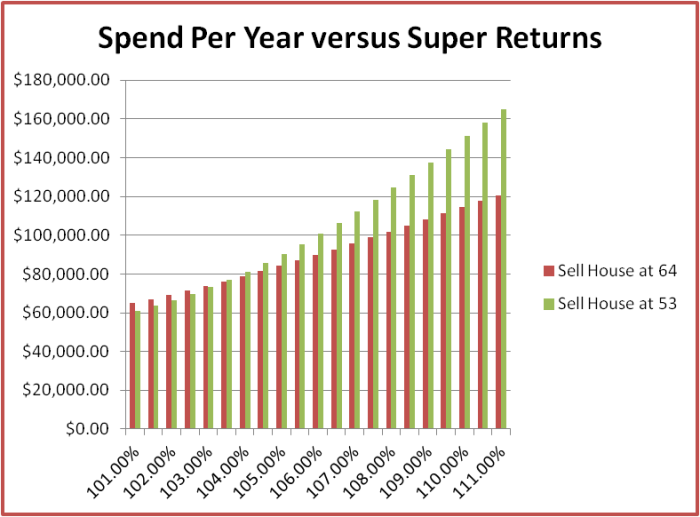

Surprisingly, there is not that much difference. If we decided to sell up at 53 and go vagabonding we would have about an extra $9K per year.

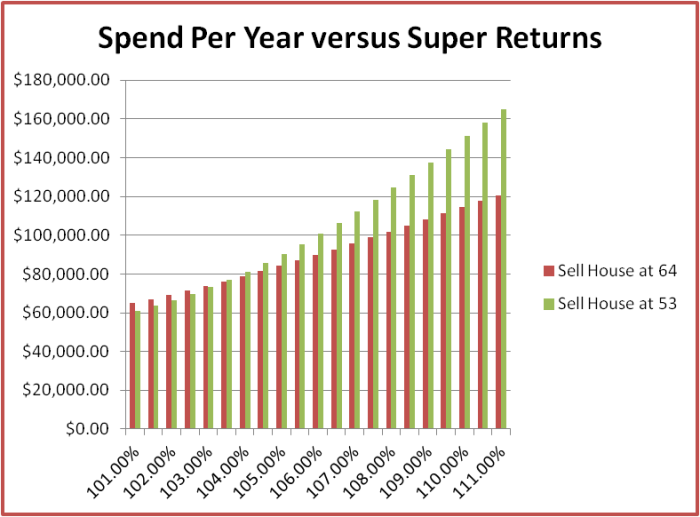

However one impact of selling your house early and putting funds into Super is that you are much more exposed to the market. If the market does well, you will have significantly higher spend. For example, if returns are 9% you will have a $137K spend if you sell your house at 53, while only $108K if you sell it at 64 with the same returns. The graph below shows the expense per year assuming a house sale at 53 versus a house sale at 64. Note that if the market performs poorly, say 1%, then selling your house early will put you in a worse position ($61K versus $65K), but not significantly worse. There is mostly upside assuming very poor returns (e.g. typical of the 70s) do not occur.

What if there was no Age pension

Some people say that you should plan as if there was no age pension. Well, if I do this, I get the graph below:

Actually not too much of a difference..

Actually not too much of a difference..

What could go Wrong?

Could we experience another decade like the 70s? Yes, I think we could. Maybe more than one decade. But we could also experience some boom decades as well. No-one really knows.

On the negative side, over the next few years we have the following happening:

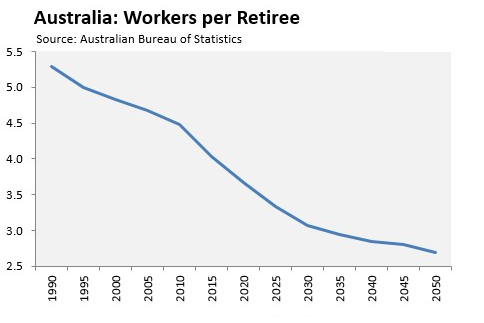

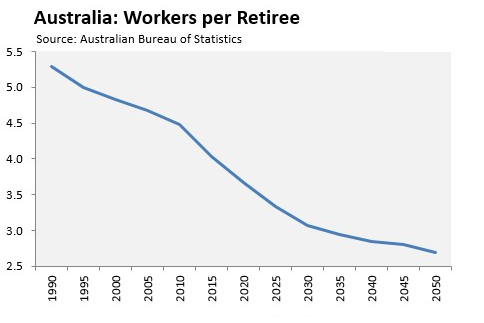

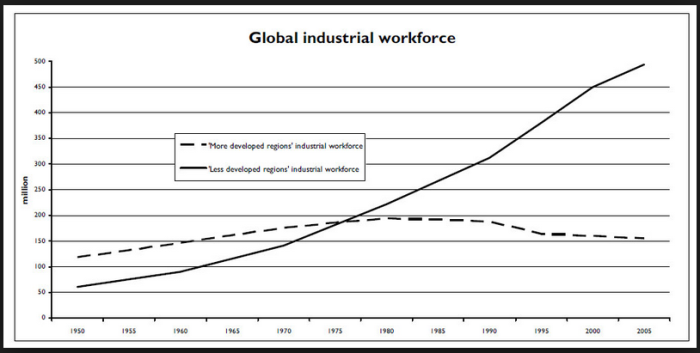

- The ratio of workers to retirees is getting smaller as the baby boomers retire. Less workers to produce goods and services and more non workers to consume them may mean that goods and services (especially services that can’t be outsourced to other countries) will become more expensive.

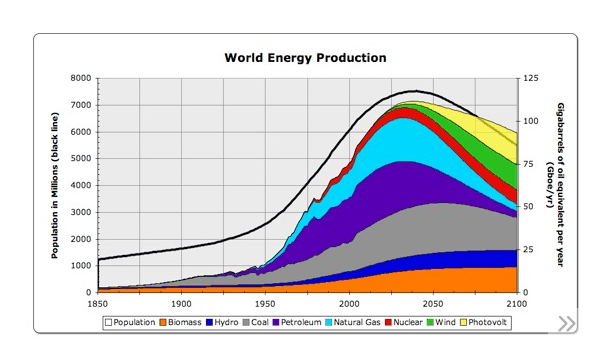

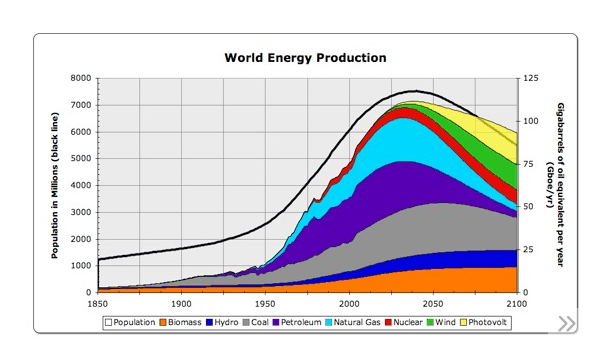

- The world is running out of fossil fuels. Goods and services may become more expensive as more expensive substitute fuels are used instead of cheap fossil fuels.

- The world is heating up and we may need to use more expensive fuels to compensate. Or agriculture could suffer in a warmer world.

- As more workers retire, the Australian government may decide to change the pension and Superannuation rules in order to reduce the social welfare bill.

On the positive side we have:

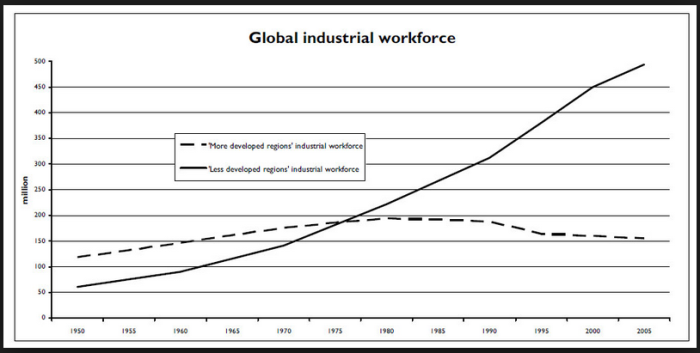

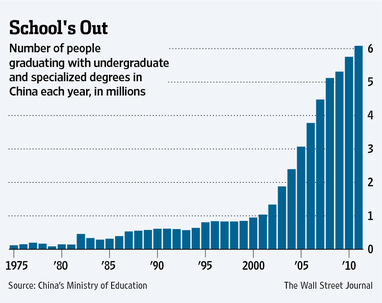

- The developing world is contributing to the world economy more and more. Things are getting cheaper as large quantities of cheap labour enter the world economy. These workers are also getting more productive as they adopt first world technology and become more educated.

- The world is becoming more connected and innovation is occurring more quickly. In addition the developing world is starting to contribute to innovation and R&D as education levels increase.

- Australian worker productivity is expected to increase over the coming years. An increase in productivity will mitigate against declining overall production caused by declining worker ratios.

All of these may effect the amount of funds available in retirement.

Conclusions

So, what are my conclusions?

- There are various tools on the Internet which help you work out when you can retire, however I have found that they are, in general not adequate to plan your retirement. They do not cater for changing spending patterns, asset sales, etc. The determined pending retiree (aka yours truly) can develop more suitable tools, but this is time consuming and requires mathematical and financial skills.

- Sensitivity analysis can be used to understand how key variables affect the average spend you can expect in your retirement. This analysis can help you make decisions such as how long to keep on working, the age at which you should plan to live on the Age Pension only, the sensibleness of spending some time in a low cost country, etc.

- Historic market performance data can be used to generate information on how you would have fared in your retirement had you retired in earlier years. This information can be used as an indication of how you are likely to fare in your actual retirement.

- It is possible to compare spending levels between a lifetime annuity approach versus an account based pension approach. Initial analysis indicates lifetime annuities do not provide good value, and should only be considered if you put a very high premium on income security or expect to live a very long time.

- It is possible to work out your spend levels assuming there is no Age Pension. This information can be handy, especially if you are concerned that the government may be cutting back on the Age Pension soon.

- If you decide to sell your house early and invest in Super, then you can expect higher spend, especially if the market does well. But of course this may come at a cost e.g. through less salubrious accommodation.

- The future is uncertain and there are various factors which are working towards making a retirement more comfortable, and others working in the opposite direction. We will have to see how things pan out.

And what am I going to do? Probably work a few more years. I work in IT, and it seems it is not that easy to get work once you get to my age, although I haven’t had any problems to date. But it’s nice to know that we should be able to retire if we want to :).

End Notes

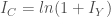

In this section I will provide information on how I have worked out the numbers behind the graphs by describing the formulas used to calculate funds in each year. It’s actually several big complex non-linear equations that need to be solved. Fortunately Excel “solver” can do just this.

A note about terminology: When I refer to “year i” below, this is the year that commences on my ith birthday.

Also, while these formula are particular to my situation, they can easily be generalized to cater for the asset sales and purchases typical in retirement.

Constants

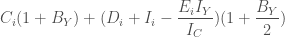

BD = Bank Cash Rate of Interest= 3.2%; This is the daily rate. BY is the yearly rate and BC is the continuous rate.

IY = Inflation = 2.73%;This is a yearly rate. IC is the continuous rate.

H = Rate of property appreciation = 2.83%; This is a yearly rate.

Variables

N = Age of selling house. M = Age of purchasing account based pension.

R = Age of Retiring. A = Age we are planning to only have rent supplementing Age pension.

Ri = Rate of Increase of Super during year i;. Ri = 5.5% for i < M, Ri = 6.0% for i >= M.

Ci = Cash at beginning of year i; Ii = Income in year i (employment + age pension);

Si = Value of Super at beginning of year i;

Pi = Value of primary residence at beginning of year i; Ti = Value of investment property at beginning of year i;

Di = Value of rent received during year i;

Wi = Estimated tax free income while working during year i.

Xi = Estimated expense while working during year i.

U = Estimated expense in first year after stopping working in 2015 dollars

V = Estimated Residual income in the year after stopping working in year 2015 dollars. i.e. any income earned in this year.

Ei = Expenditure during year i in year I dollars. Ei is of interest as these are used to plot the graphs.

Initial Conditions

C52 = $595,000; S52 = $520,000; P52 = $1,029,000; T52 = $250,000; D52 = $5000;

R = 52, N = 64, M= 60, A = 90,

if R > 52 then W52 = $120,000 else W52 = 0

if R > 52 then X52 = $40,000 else X52 = 0

U = $40,000, V = $20,000,

What we are trying to solve for

We are looking for the values of:

ER+1 that minimizes SA.

Subject to:

SA > 0,

> 0

> 0

SN – PN > 0

That is, we want to work out the expense in year R+1 (the year after retiring) that minimizes the amount of funds we have left at 90, subject to:

- Funds left at 90 must be greater than zero.

- The year before taking out the account based pension, our Cash and income must be more than our expenses. That is, we need to make sure that our expense levels prior to getting access to the account based pension don’t cause us to run out of money.

- The amount of Super left at the end of the year before selling the house must be positive. That is, we need to make sure that our expense levels prior to getting access to the additional fund from selling the house don’t cause us to run out of Super.

We also want to find EM that minimizes SA.

Subject to:

SA > 0,

SN – PN > 0

That is, we want to work out the expense in year M (the year during which we start on the account based pension) that minimizes the amount of funds we have left at 90, subject to:

- Funds left at 90 must be greater than zero.

- The amount of Super left at the end of the year before selling the house must be positive

and lastly

EN that minimizes SA.

Subject to:

SA > 0.

That is, we want to work out the expense in year N (the year during which we have access to the funds from the house sale) that minimizes the amount of funds we have left at 90, subject to:

- The amount of Super left at the end of the year before selling the house must be positive.

These Solvers need to be done in the order in which the events causing the assets to change occur (e.g. if I sell my house before accessing Super, then this one should be done first, and the boundary conditions will also need to change to reflect this).

Formula

First the easy ones:

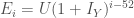

(i)

The investment property appreciates every year.

(ii) if i < N then  else

else

The primary residence appreciates every year until it is sold when I am 64.

(iii)

Rent from investment property increases with inflation.

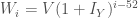

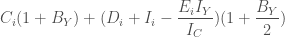

(iv) (a) Except for i+1 = M, N and R+1, for i >= R,

where M69=0.9; M79=0.9 and Mi=1 for all other i. ER+1, EP and EN are derived from solver equations described above.

That is, expenditure goes up with inflation each year, but is reduced by 10% at 70, and another 10% at 80.

(b) If R > 52 then for i < R, Ei = Xi

(v) For  ,

,

Year after retiring, I spend U.

(vi) If i < R then  else

else

(vii) If i < R then  else

else

(viii) if i = R then

Working income and expenses increases with inflation, and become zero when I retire.

(ix) For i < 67, Ii = Wi

Income is employment income prior to 67.

Now for the more complicated ones. Here is the formula for Cash at beginning of year i+1:

(x) if  < 0 then Ci+1 = 0

< 0 then Ci+1 = 0

else

where

and

This says that if the cash at beginning of year i + rent received during year i + Income received during year i + interest on cash during year i is less the amount spent during year i, then the cash in year i+1 is zero. Otherwise it is the cash at beginning of year i + rent received during year i + Income received during year i + interest on cash during year i less the amount spent during year i. Note that in the year that expense exceeds cash that is non-zero, the excess Cash is added to Super for that year only.

And here is the formula for Super at the beginning of year i+1:

(xi) if  > 0 then

> 0 then

else

This says that if expenses is less than cash + other sources of income for the year, then Super just increases at the super return rate. This is because cash will be used to fund expenses while it is available. Otherwise to work out the new super value we need to deduct expenses and add in any income and then multiply by the Super return rate. Note that if we cannot fund expenses from Cash then Cash will be zero for all years except the first year where this occurs. So, I have added in Cash to working out the new value of Super; this will be zero for all years except the first year, where I have assumed that the Cash will be added to the Super pot. I’ve also added in the value of the house when I sell it.

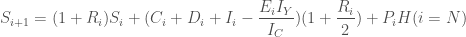

Now for the most complicated one. Working out the age pension.

For this one we have the following variables:

PULi = If your assets are above this at the start of year i, then there is no part pension.

PLLi = If your assets are below this at the start of year i, then you get the full pension.

PFPi, = Value of full pension at the start of year i

PILi = If you earn more than this income per fortnight during year i, then your pension will be reduced.

QLLi = If your assets are below this in year i, then they will be deemed to earn income 2%. Additional assets will be deemed to earn income at 3.5%.

Qi is the deemed income in year i; DAi is the deduction in the pension due to assets in year i. DIi is the deduction in the pension due to income in year i.

We have these initial conditions:

PUL52 = $1,144,500; PLL52 = $286,500; PFP52 = $33,448; PIL52 = $248; QLL52 = $79,600

And these formula:

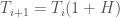

(xii) PULi+1=PULi (1 + IY);

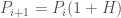

(xiii) PLLi+1=PLLi (1 + IY);

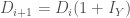

(xiv) PFPi+1 = PFPi (1 + IY);

(xv) QLLi+1 = QLLi (1 + IY);

(xvi) PILi+1 = PILi (1 + IY)

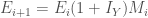

These say that the pension will go up with inflation (rather than Average Weekly Earnings), and that all limits will also go up with Inflation.

Here is the assets test:

(xvii) if Ci + Si + Ti > PULi then

DAi = PFPi

else

DAi = PFPi – MIN(PFPi (PULi – Ci – Si – Ti) / (PULi-PLLi), PFPi)

This says that if your assets (Cash + Super + Housing investment) are greater than the upper limit on pension eligibility, then the deduction is equal to the full value of the pension. Otherwise the deduction is computed according to where your assets are between the upper limit and the lower limit.

Now for the incomes test:

(xviii) If Si < QLLi then

Qi = 0.02 Si

else

Qi = 0.035 (Si – QLLi) + 0.02 QLLi

This is just working out the value of deemed income.

(xix) if (Qi + Di) /26 > PILi then

DIi = 26 MIN(0.4 ((Qi+Di)/26 – PILi), PFPi /26)

else

DIi = 0

This is saying that if your income (deemed income + rent) is less than the lower limit on income, then the Income deduction is zero, otherwise it is the value over the limit multiplied by 0.4.

Finally we have:

(xx) If i >= 67,

Ii = PFPi– MAX(DAi, DIi)

This says that you don’t get the pension until 67, and that when over 67 income is equal the pension less the maximum of the income deduction and the assets deduction. I assume by 67 I have stopped working.

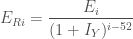

Converting to 2015 Dollars

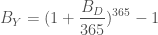

All values to date are in nominal dollars unadjusted for inflation. It’s not too hard to workout the formulas for real values.

Let ERi = Value Expenditure during year i in 2015 dollars; IRi = Value of Income in year i (employment + age pension) in 2015 dollars

Then

(xxi)

(xxii)

Actually not too much of a difference..

Actually not too much of a difference..